Invisible Transatlantic Encounters: Anna Lesznai and Mariska Undi

Rebecca Houze

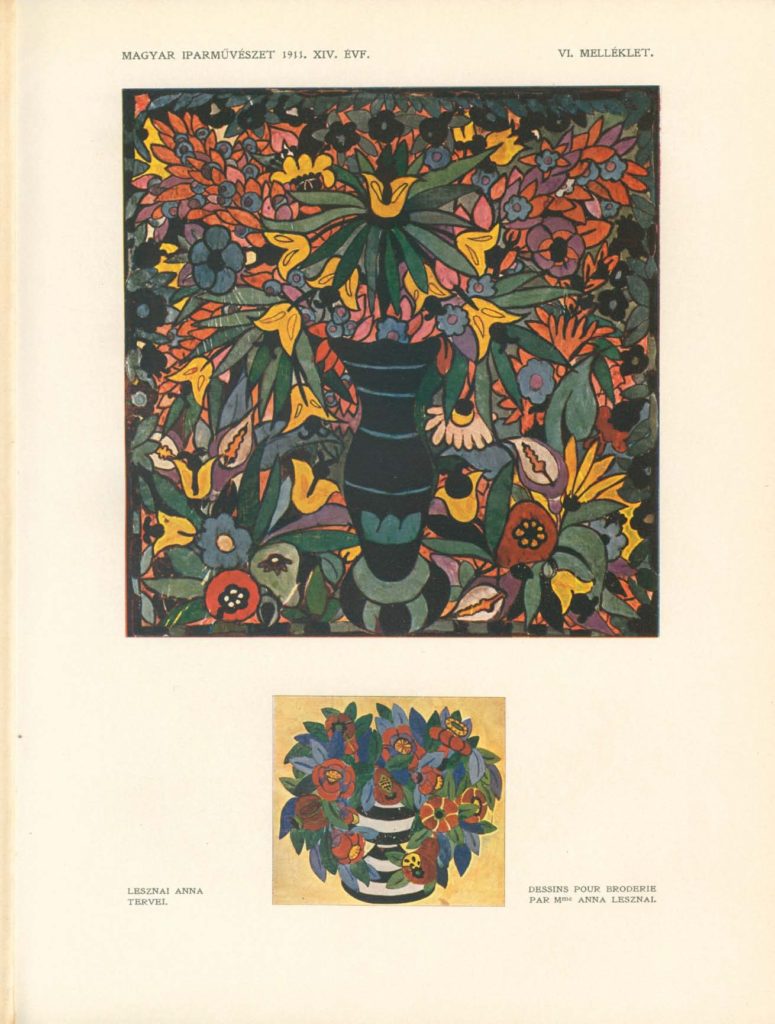

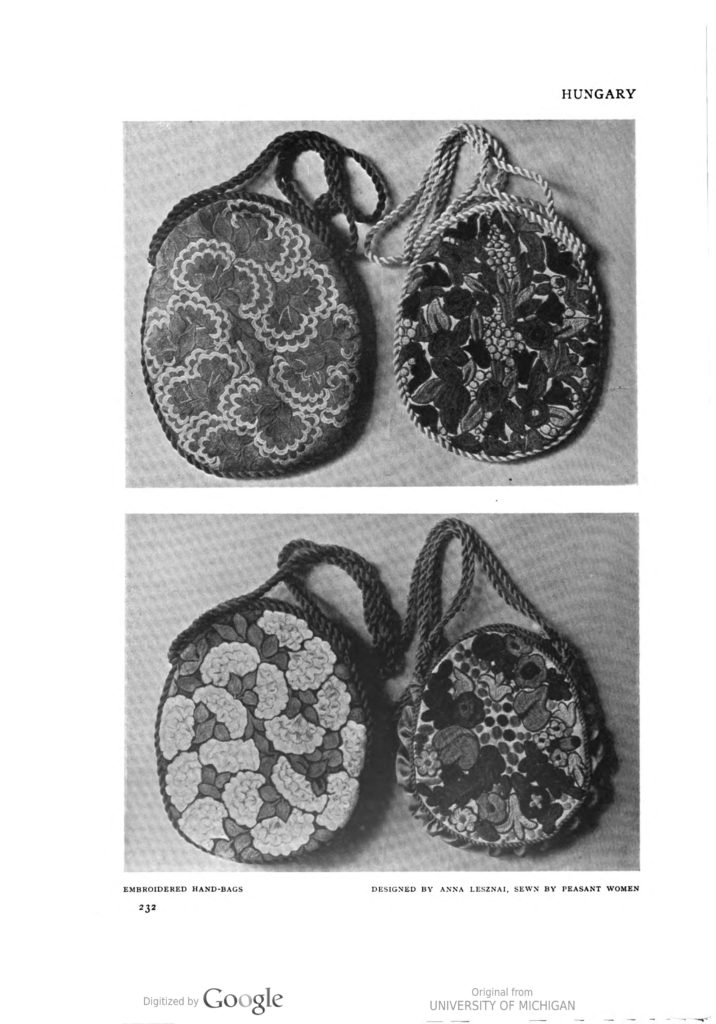

When I first learned about From Vienna to the World, I thought immediately of Anna Lesznai (Amália Moskowitz) (1885-1966) a Hungarian poet, painter, and teacher. Lesznai was born in Budapest, lived in Vienna for many years in political exile, and then moved to New York in 1939 to escape the Holocaust. Like many of her contemporaries, Lesznai emigrated from Central Europe to the United States, bringing her talents and ideas with her. Over the past few years I have had the opportunity to spend some time in Hungary to learn more about Lesznai by exploring her papers and other work in the Petőfi Literary Museum in Budapest and visiting the Hatvany Lajos Museum in Hatvan, so her story was fresh in my mind. I had been hoping to better understand Lesznai’s motivations for working with women in Hungarian villages to produce stylish handbags and pillow covers with colorful motifs reminiscent of the flower patterns in Matyó embroidery—a tradition that is now acknowledged by UNESCO as an example of intangible cultural heritage (Figures 1. and 2.).[1]

Lesznai’s appropriation of Matyó folk culture is just one example of the widespread fascination with the “primitive” that influenced the work of so many European modernists in the early twentieth century. But I wondered if there was something more to her interest in it, as someone who was frequently marginalized as a woman, a Jew, and a refugee. And how did Matyó embroidery and other themes of European folk life, to which Anna Lesznai had such a personal—indeed a spiritual—connection, shape her professional trajectory after she crossed the Atlantic?

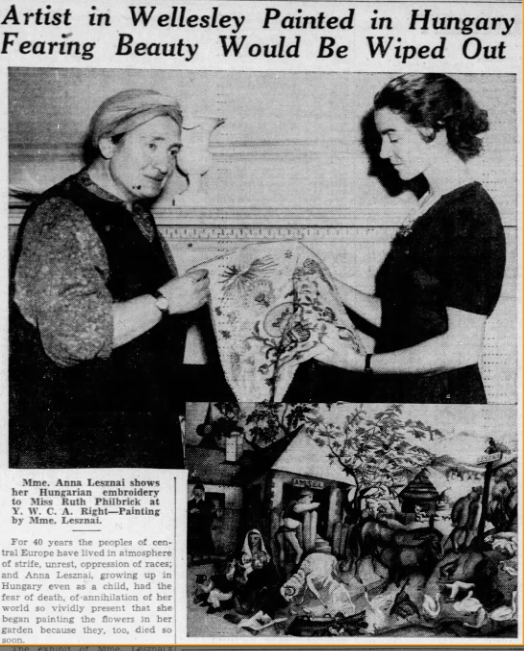

Like other European women émigré designers from Austria-Hungary, born around the turn of the twentieth century, Lesznai had to reinvent herself and develop new contacts once she arrived in the United States. She presented lectures at various venues, including in Sandusky, Ohio, near Oberlin College, where her second husband, the historian and social scientist Oszkár Jászi (1875-1957) was a professor; at Wellesley College, a progressive women’s liberal arts college in Massachusetts; at the Boston YWCA (Young Women’s Christian Association), an organization that had long provided outreach to immigrant communities (Figure 3) ; at the Newark State Teachers College in Newark, New Jersey; and in New York City, where, according to several sources, she opened her own school of painting.[2] Lesznai’s third husband, Tibor Gergely (1900-1978), with whom she emigrated to the United States, had a successful career as an illustrator for the Little Golden Books series published by Simon & Schuster, and both Lesznai and Gergely produced covers for The New Yorker magazine.

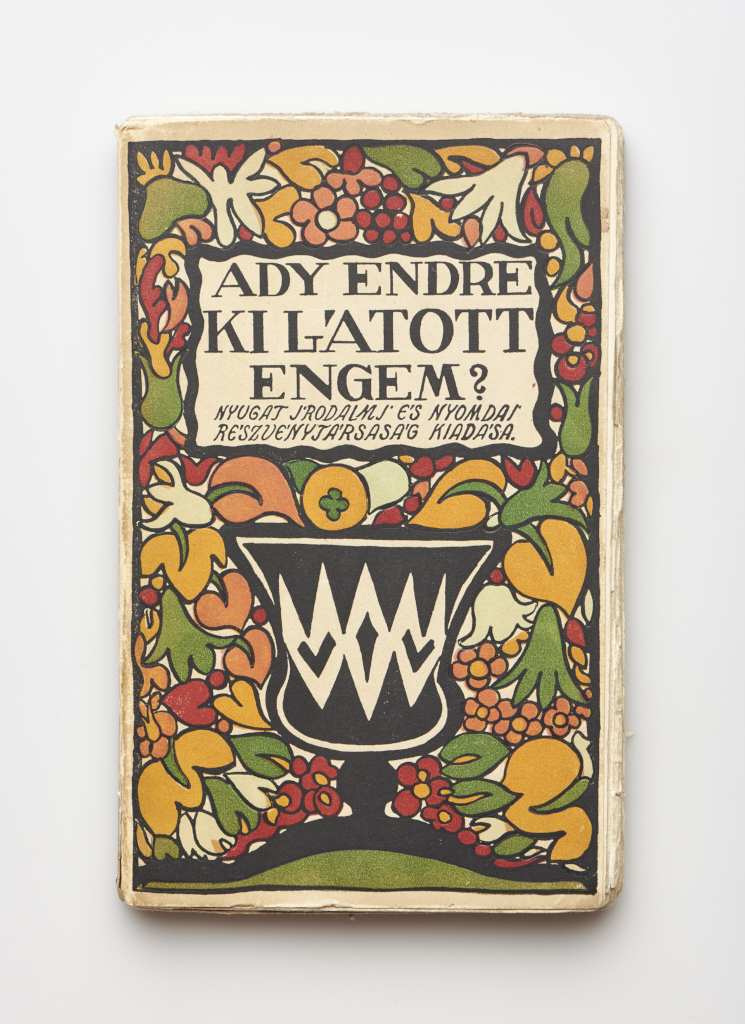

Anna Lesznai was a member of the famous Sunday Circle led by Marxist theorist György Lukács. Over the years, scholars have been drawn to her numerous connections to progressive social and literary circles and to her personal relationships with feminists, socialists, artists, and thinkers during the period of her youth and exile in Europe (Figure 4).[3]

Less, however, seems to be known of her career in the United States.[4] A few years ago I borrowed a library copy of the German translation of Lesznai’s autobiographical novel, Kezdetben volt a kert (In the Beginning Was the Garden), which was published in 1965, a year before the Hungarian edition was released. The library book contained a hand-written inscription, “To Julia and Hans Fybel, mit treuer Freundschaft und Liebe, Máli, Nov. 1965.”[5] Who were those dear friends, I wondered, and what more could I learn about Anna Lesznai by tracing the personal and professional connections revealed in her charming dedication?

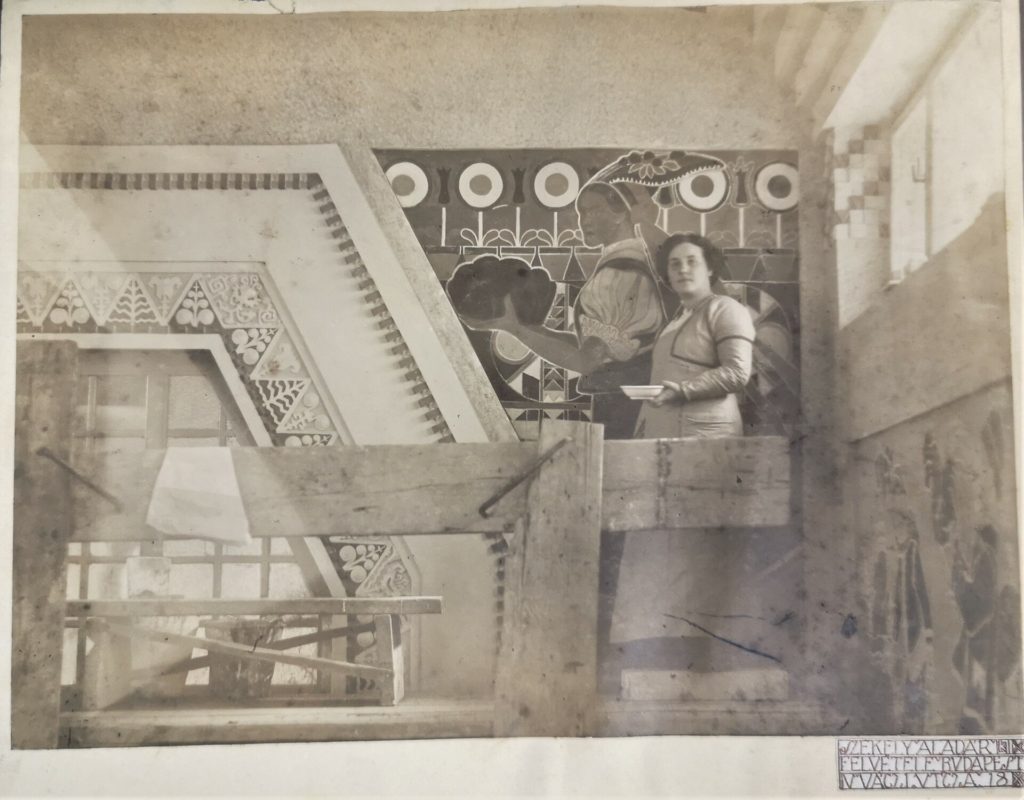

My current research on Anna Lesznai is part of a larger project, which compares her activities to those of her Hungarian contemporary, Mariska Undi (Mária Springholz) (1877-1959). Unlike Lesznai, Undi did not emigrate. Rather, she pursued a career as a designer and teacher in Budapest through the interwar and postwar period, when Hungary was no longer a part of the sprawling Central European monarchy (Figure 5). Although Lesznai and Undi were interested in many of the same subjects, including folk embroidery, children’s book illustration, and feminism, their social and professional circles do not seem to have overlapped (Figure 6).[6] Whereas Lesznai was connected to the Nyolcat group of painters in Budapest and to the Viennese exhibition societies Hagenbund and Wiener Frauenkunst, Undi was affiliated with the Gödöllő colony, which was devoted to spiritual renewal through a revival of arts and crafts.[7] Her one well-known transatlantic encounter was in 1904, when she exhibited her work together with fellow Gödöllő designers at the St. Louis World’s Fair, a venue that also featured many women designers from Vienna’s School of Applied Art.[8]

Although designers in Vienna and in Budapest at the turn of the twentieth century were engaged in similar projects, from the Gödöllő art colony to the Wiener Werkstätte, they reported on one another’s activities only infrequently and seem to have crossed paths rarely, if ever, despite the fact that the two cities on the Danube are just a two-hour train ride apart. Because the psychological distance between those two creative capitals was so vast, however, it may have been left to individuals with a more cosmopolitan perspective to cast a light on both, such as Amelia Sarah Levetus (1853-1938), the Jewish British-Austrian correspondent for the International Studio, who frequently reported on women designers from both urban and rural parts of Austria-Hungary.[9] Refracted through the spaces of international exhibitions, like the St. Louis World’s fair, the complexities of Central European design—especially that produced by women designers—comes into sharper focus.

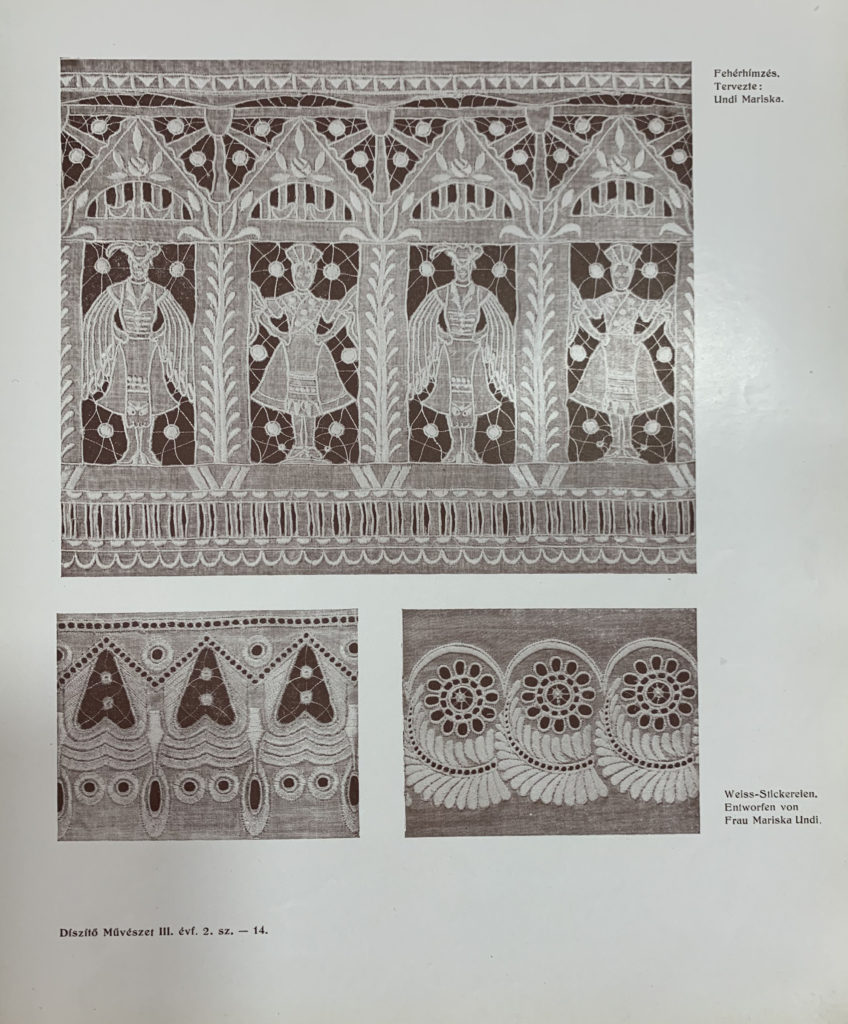

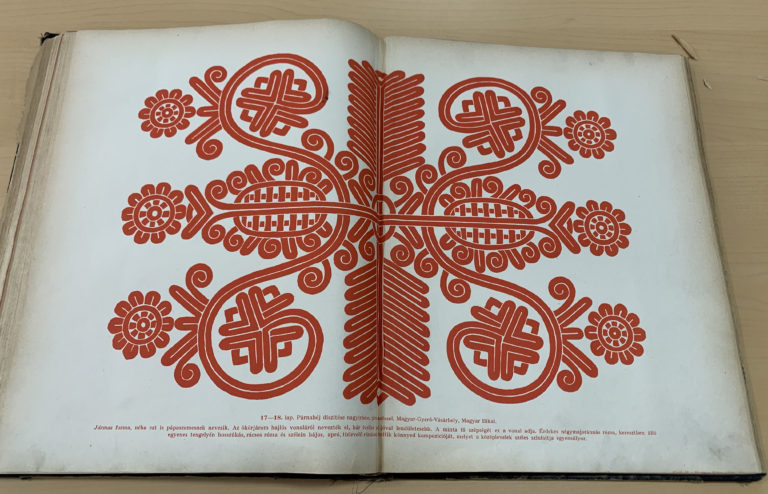

The relationship between Lesznai and Undi may be most visible in their pedagogical activities, though, in both cases, this aspect of their work needs more research. Undi’s archive, held by the Gödöllő Town Museum, includes sketches, photographs, and an array of textile samples that she collected during her extensive research trips. This material formed the foundation of her books Magyar kincsesláda (Hungarian Embroidery Treasure Box) prepared as part of the school curricula for the Hungarian Ministry of Education, and Hungarian Fancy Needlework, which was published in English for an international audience (Figures 7-8).[10]

Undi was a passionate advocate for the inclusion of traditional needlework techniques in school curricula as a means to preserving Hungarian cultural heritage after the 1920 Treaty of Trianon, which ceded nearly two thirds of the geographic territory occupied by Hungary before the war to Romania, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Austria.

Before she immigrated to the United States, Lesznai taught in the workshops of painter Desző Orban (1884-1986), previously a member of the avant-garde Nyolcat group with whom she had first exhibited her work. Orban’s workshop offered classes on art and design for the general public.[11] And, according to Petra Török, it was in part an invitation to present lectures on Hungarian folk art at the International School in Sandusky, Ohio, which led Lesznai to depart for the United States in 1939.[12] The school’s founder, Elma Pratt (1888-1977), an enthusiast of diverse folk cultures and entrepreneurial educator, had included Lesznai’s work in a 1935 exhibition of modern applied art at the Brooklyn Museum in New York and may have crossed paths with her in Europe on one of Pratt’s visits to Mezőkövesd to see the colorful Matyó embroidery that had inspired Lesznai’s own designs.[13] Lesznai’s poignant teaching notes and unpublished manuscript written after she immigrated to the United States for an audience of art educators reveal her highly personal interpretation of design as a universal restorative activity in a tragically broken world.[14]

How might we learn more about émigré designers like Lesznai by examining their work in relationship to those like Undi, whose ideas may have crossed the Atlantic, but who continued living in Europe? How did the personal and professional circumstances of Lesznai and Undi differ? How did the extraordinary pressures that directed Lesznai from Budapest to Vienna and New York lead her to a career path that was different than Undi’s in some ways and similar in others? Although Undi remained in the same place, the world around her shifted. After the First World War Hungary was no longer a part of Austria-Hungary, and many of its historic regions, which had been known for their rich folk art, were no longer a part of Hungary. Perhaps it would be fruitful then to consider not only the more visible transatlantic encounters stemming from Vienna, such as Lesznai’s journey to New York, but also the less visible exchanges of ideas between artists in the larger sphere of Vienna’s cultural influence.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Elana Shapira for first inviting me to present a paper on a Jewish Hungarian woman textile designer for her 2019 symposium at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. The result of that research is “The Art and Design of Anna Lesznai: Adaptation and Transformation,” in Designing Transformation: Jews and Cultural Identity in Central European Modernism, edited by Elana Shapira, 173-188 (London: Bloomsbury, 2021). An essay on Mariska Undi’s ethnographic activities, “A Hungarian Treasure Chest: The Art Colony at Gödöllő in Critical Perspective,” in Constructing Race on the Borders of Europe: Ethnography, Anthropology, and Visual Culture, 1850-1930, edited by Marsha Morton and Barbara Larson, 149–66 (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021), originated in a panel chaired by Alison Morehead at the 2018 College Art Association conference, which was sponsored by the Historians of German, Scandinavian and Central European Art. Work in progress was presented at the International Conference on Design History and Design Studies (ICDHS) in Barcelona in 2018 and at a symposium of Centre for Contemporary and Modern Art and Theory at Masaryk University in Brno in 2022. I extend my deepest thanks to the many colleagues and friends who have so generously contributed to this research, especially to Katalin Géller, Katalin Keserű, Mónika Lackner, Cecília Nagy, Agnes Prépoka, and the Hungarian Fulbright Commission, which supported this project.

[1] UNESCO. “Decision of the Intergovernmental Committee: 7.COM 11.15.” Seventh Session of the Intergovernmental Committee (7.COM) for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO Headquarters, 2012. https://ich.unesco.org/en/Decisions/7.COM/11.15. See also Julia Secklehner, “Crossing Borders and Period Boundaries in Central European Art: The Work of Anna Lesznai (ca. 1910-1930).” In Rethinking Period Boundaries: New Approaches to Continuity and Discontinuity in Modern European History and Culture, edited by Lucian George and Jade McGlynn, 119–48. Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2022 and “The Birth of Painting from the Spirit of the Gingerbread: Anna Lesznai’s Hungarian Exotic in 1920s Vienna.” In Erasures and Eradications in Modern Viennese Art, Architecture and Design, edited by Brandow-Faller and Laura Morowitz, 129–42. London: Routledge, 2023.

[2] Fiona Stewart, “‘In the Beginning Was the Garden’: Anna Lesznai and Hungarian Modernism, 1906-1919.” Ph.D. Dissertation, York University, 2011, p. 9, n. 13.

[3] Notable is the research of Petra Török and Judit Szilágyi. See, for example, their special issue of Enigma, nos. 51-52 (2007). See also the work of Judit Szapor, Hungarian Women’s Activism in the Wake of the First World War: From Rights to Revanche. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018, and, from a more critical perspective, Anna Menyhért, Women’s Literary Tradition and Twentieth-Century Hungarian Writers: Renée Erdős, Ágnes Nemes Nagy, Minka Czóbel, Ilona Harmos Kosztolányi, Anna Lesznai. Translated by Anna Bentley. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

[4] One notable exception to this is the work of Zoltán Fejős, who has researched early exhibitions of Anna Lesznai’s work in the United States, long before she herself moved to New York. See Zoltán Fejős, “Hungarian Folk Art Exhibitions in the USA in 1914.” Hungarian Studies Review 44, no. 1–2 (Spring-Fall 2017): 5–35 and “‘Üjszerű mint a futuristák munkája’ Magyar népmúvészeti kiállítás Amerikában 1914-ben” (“Artful as the Work of Futurists.” An Exhibition of Hungarian Folk Art in America in 1914). Néprajzi értesíto 97 (2016): 87–204.

[5] Anna Lesznai, Spätherbst in Eden: Roman. Edited by Ernst Lorsy and Hilda von Born-Pilsach. Karlsruhe: Stahlberg Verlag, 1965. Copy in the University of California Los Angeles library.

Clotilde Julia Fybel (neé Scharvogel) (1880-1969) was an American textile artist and translator born in Leipzig. She was married to Hans Joseph Fybel (Feibelmann) (1897-1994) who was born in Zurich. Käthe Recheis, No Room for the Baker, trans. Julia C. Fybel. New York: Four Winds Press, 1969. Illustrations by Tibor Gergely. So far, I’ve come across just two examples of Julia Fybel’s textile design: “Child with Cat (Mise-en-carte),” textile design in crayon and graphite on paper, dated to the mid-20th century, and a knitted wool hanging from the 1950s, both in the collections of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Data available online: https://music.si.edu/object/chndm_1971-31-3 and https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18475095/.

[6] My research has yet revealed just one exhibition featuring the work of both artists. Their names are mentioned in a brief review of works exhibited in 1921 by the Hungarian Bibliophile Society at the Museum of Applied Arts in Budapest. G. E., “Gyermek-képeskönyvek kiállitása.” Az Ujság 19, no. 246 (November 3, 2021), p. 4.

[7] Katalin Gellér, “Mariska Undi (1877-1959) Painter and Applied Artist.” In Women at the Gödöllő Artists’ Colony, edited by Zsofia Németh, 24–32. London: Hungarian Cultural Centre, 2004.

[8] The official catalogue lists the names of twenty-one women exhibitors in the Austrian applied arts section. See Frederick J. V. Skiff, Official Catalogue of Exhibitors. Universal Exposition St. Louis, U.S.A. 1904. Division of Exhibits. Dept. B. Art and Dept. D. Manufactures. St. Louis: The Official Catalogue Company (Inc.), 1904. On the Hungarian exhibits in St. Louis see my essay “‘A Revelation of Grace and Pride’ Cultural Memory and International Aspiration in Early Twentieth-Century Hungarian Design.” In Expanding Nationalisms at World’s Fair’s: Identity, Diversity and Exchange, 1851-1915, edited by David Raizman and Ethan Robey. London: Routledge, 2017; and on the relationship of the Gödöllő colony to the broader arts and crafts movement more broadly see Juliet Kinchin, “Hungary: Shaping a National Consciousness.” In The Arts and Crafts in Europe and America, 1880-1920: Design for the Modern World, edited by Wendy Kaplan, 142–77. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2004. Katalin Keserű’s groundbreaking essay, “The Workshops of Gödöllő: Transformations of a Morrisian Theme.” Journal of Design History 1, no. 1 (1988): 1–23, remains an important resource.

[9] See for example A. S. Levetus, “The Imperial Arts and Crafts Schools, Vienna.” International Studio 30, no. 120 (February 1907): 323–34; A. S. Levetus, “Stickereien Der Lipa Volksindustrie-Aktien-Gesellschaft.” Textile Kunst und Industrie 7, no. 8 (1914): 337–47.

[10] Mária Undi, Hungarian Fancy Needlework and Weaving. Budapest: Stephaneum Press/ Mariska Undi, 1934; Mariska Undi, Magyar kincselsláda; muvészi, eredti rajz- és himzésminták gyüjteménye/ Hungarian Embroidery Treasure Box/ Originelle Ungarische Volksstickereien. 10 vols. Budapest: Szerzo, 1932. A large part of the collection was presented to the museum by Mariska Undi’s niece, Flóra Undi. Those works contributed to a retrospective exhibition of her work in 1996. See Gellér, Katalin. Undi Mariska gyűjteményes kiállítása a Gödöllői városi múzeumban. Gödöllő: Városi Múzeum, 1996. A second exhibition was held in 2014: Flora Undi and Katalin Gellér, Undi Mariska családja és művészete: az Undi-lányok (Mariska Undi’s family and art: the Undi girls). Budapest: Püski Kiadó, 2014.

[11] Desiderius Orban interviewed by Denise Hickey in Denise Hickey collection [sound recording], 1971. National Library of Australia. Available online: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-193497629/listen

[12] Petra Török, “Ornamenssé váltott sors—művészeti és irodalmi otthonteremtés Lesznai Anna életművében” (Fate into Ornament: Creating an Artistic and Literary Home in the Oeuvre of Anna Lesznai). Ph.D. Dissertation, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, 2012, 122. I am grateful to Zoltán Fejős for sharing this reference with me.

[13] Cardassilaris, Nicole Ruth. “Bringing Cultures Together: Elma Pratt, Her International School of Art, and Her Collection of International Folk Art at the Miami University Art Museum.” MA Thesis, University of Cincinnati, 2007. Another of Pratt’s guest artists was Emmy Zweybrück-Prochaska (1890-1965).

[14] “The teaching of Art can never be more important than in a time when science and politics, technics, and social organization err in the dark and have lost the way which guides towards human happiness and reason.” “Lesznai Anna írásai és jegyzetei” (Anna Lesznai’s writing and notes in English), n.d. Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum (PIM) Inv. no. V.3670/35. See also Anna Lesznai, “Creative Design Course for Elementary and Secondary School Teachers. Fifteen two-hour lessons. February 4 – May 19, 1948.” Book manuscript. PIM Inv. no. D1.618; Anna Lesznai, “Peasant Art,” n.d. PIM Inv. no. V.3670/34; Anna Lesznai, “Notes on Art Methodology—Lectures,” n.d. PIM Inv. no. V.3670/29.