The Transnational Encyclopedia.

An nterview with Holly Phillips, a collection manager and acquisitions specialists at the Thomas J. Watson Library Museum

Julia Harasimowicz

Holly Phillips, a collections manager and acquisitions specialist, discusses the library’s international mission, partnerships with organizations abroad, and the special exhibit Artists of the Holocaust, which showcases a one-of-a-kind collection of testimonies from Eastern and Central Europe.

The Thomas J. Watson Library, situated within the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is one of the most comprehensive art history libraries in both the United States and the world. The library was established in 1870, the year the museum was founded. With a physical presence since 1880, it now houses more than 1,020,000 volumes. Among its collections are reference books, auction and sale catalogs, rare books, manuscripts, artists’ publications, digital collections, and much more. The institution’s main objective is to support The Met’s staff members in their studies, but the library has also evolved into a vital research location for art investigators and artists from all corners of the globe. Over the past few decades, it has digitized many of its collections, including not just The Met’s publications but also auction catalogs and source documents

Julia Harasimowicz: The “Vienna to the World” project is about the exchange of knowledge and art between Europe and the United States but also has the much broader purpose of telling international stories and presenting methodologies for research on migration and the globalization of European art. As one of the most prominent art history libraries in the US, the Thomas J. Watson is an exceptionally important site for the recognition of these transatlantic connections.

Holly Phillips: Watson Library supports the encyclopedic collections at The Met, so our holdings are expansive representing the entire scope of the history of art. Our research collection has been making international connections for years. I think this culminates now in the beautifully renovated and newly arranged European Paintings galleries. Especially now, we are making global connections more than ever before.

What are your tasks as a collections manager of such an extensive collection?

I participate in a few different areas of Watson Library. One area that I oversee is the gifts. Sometimes, we receive a gift as an important catalog from, for example, an artist. They will typically send us their catalogs because they are interested in being represented in the library. But these gifts range from one catalog to collections of over 2,000 books and more, many of which tend to be subject-based. I also work very closely with the Arthur K. Watson Chief Librarian, Ken Soehner and Jared Ash, Florence and Herbert Irving Museum Librarian, Collection Development acquiring rare research material. I also supervise a phenomenal team of volunteers and interns who support many of our projects and initiatives.

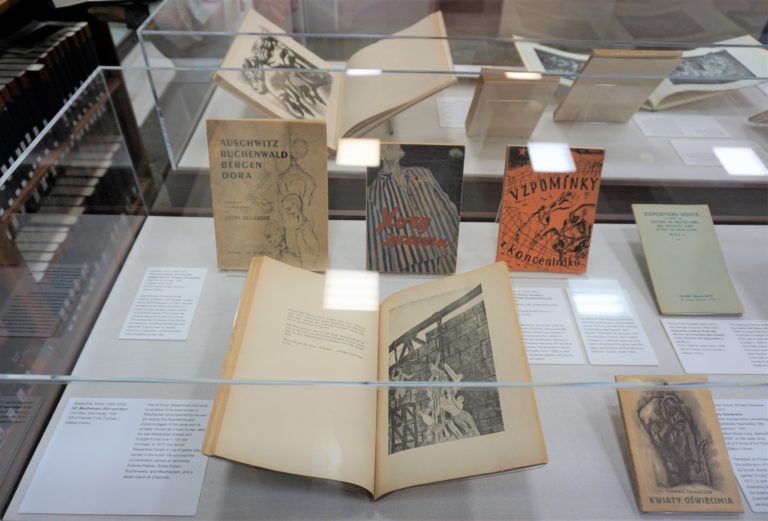

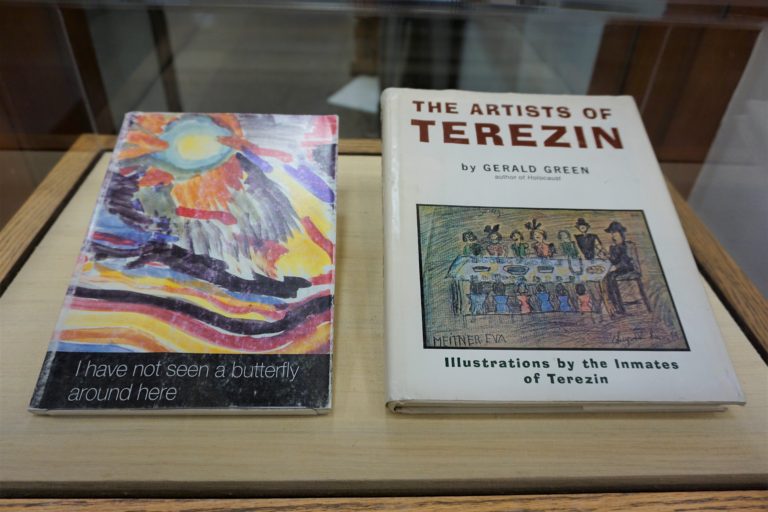

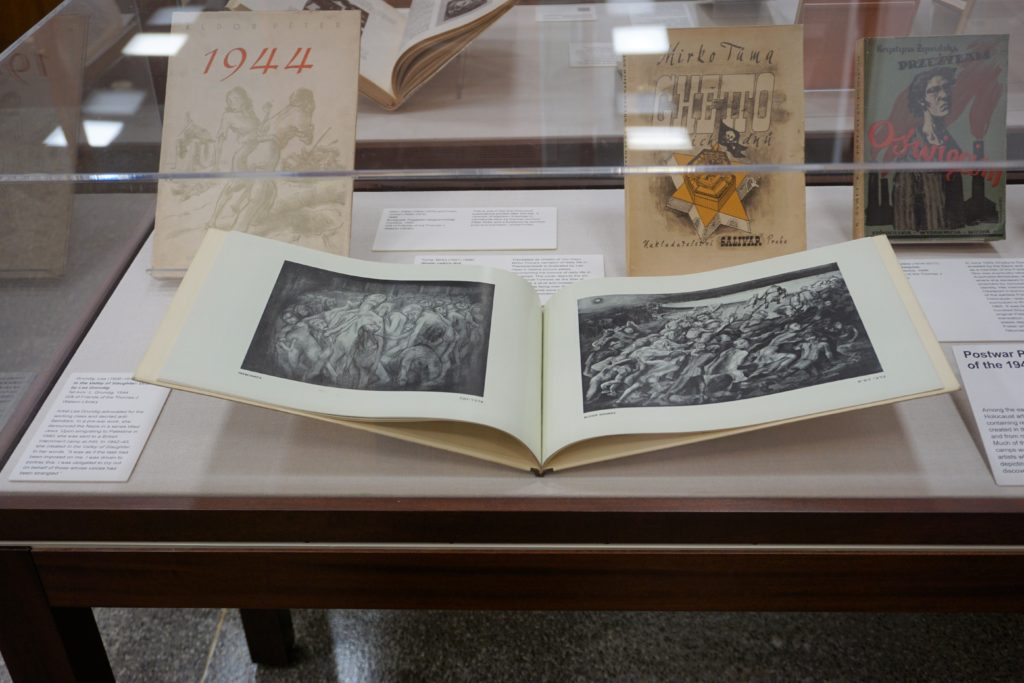

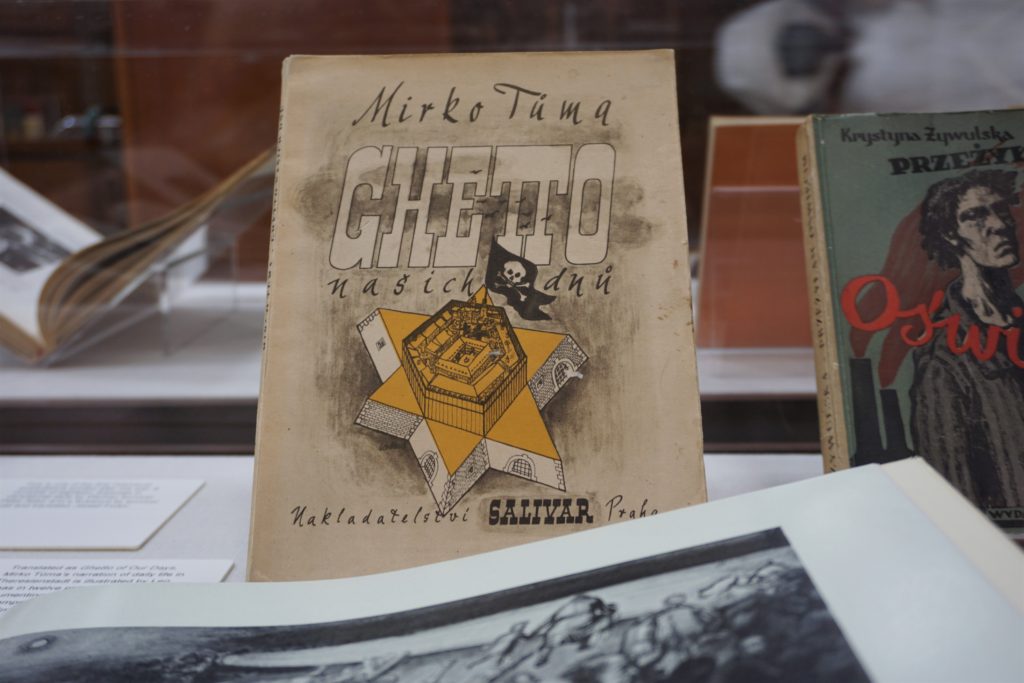

Moreover, for a long time, I I have been organizing many of our vitrine displays, with much support from my team members. I recently curated “Artists of the Holocaust: Portfolios, Exhibition Catalogs, and Monographs“. We also have a corresponding online exhibition that reflects what you see in person. And now we are happily on the official calendar of The Met as the curatorial exhibitions, we are very excited about that!

What does the acquisition process look like in an institution with a 150-year history? How do you research the provenances of the objects you include in your collection?

We are a research library, actually one of the largest art history research libraries in the world. Our job is to acquire research material for both our curators and the museum staff. We do not necessarily research the books per se, other than for exhibitions when we have them on display. However, we have a brilliant cataloging team, and we pride ourselves on having catalog records as detailed as possible, including putting in as many keywords, as many subject headings so that the researcher will be able to find what they are looking for in our online holdings as easily as possible. We also have a blog series In circulation of different team members writing interesting essays on the books.

How do you help foreign researchers access materials?

In addition to The Met’s staff, we are also open to the public, registering thousands of new patrons each year. We want our researchers to feel comfortable and have access to all the necessary art historical research materials. Our patrons work at auction houses, they are Ph.D. students, interior designers, and filmmakers, among many other fields… So, our role is to provide the material, monographs, catalogs raisonnés, trade catalogs, and all different kinds of books for study.

We were not always so accessible to the public. We used to be open mainly to professionals, Ph.D., or graduate students, but our chief librarian, Ken Soehner, felt that it was important to change that. In the early 2000s, he decided to open it up to the broader public, including young college students, and that was a wonderful and meaningful decision.

Do you collaborate with institutions and researchers based outside the Americas?

We have many international research collaborations. One example is our Contemporary Catalogs Project which we started in 2001. We assembled a team of interns and volunteers to identify galleries around the world with strong exhibition catalogs. We started reaching out to those places as early as 2001 and enquiring if they would consider donating their publications to us. That was another example of brilliant foresight by Ken Soehner. The library’s task has become not only to represent current living artists but also to preserve material for future generations. As a good example, when I first started working in the library in 1995, we still did not have certain key texts, including Andy Warhol, and Yves Klein. Only now do we know how necessary it is. Thus, our Contemporary Catalogs Project has grown, we have received over 24,000 catalogs, both print and PDF.

As part of your international mission, you were one of the first institutions worldwide to begin processing collections using digital technologies.

Yes, we have a very strong digitization program which is very important and key to us. We started that in the early 2000s, we researched the best equipment, and since then we have digitized as many books as we can within copyright law. You can find our collections and search our digital holdings through the main Watson page in the section for digital collections.

I must admit that for an early career researcher from Eastern Europe studying transatlantic and, more generally, international connections, the availability of historical resources online is often the only way to conduct a study.

For us, accessibility goes hand in hand with customer service. In addition to digitizing material since the early 2000s, during the pandemic when everybody was staying at home and working remotely, we have changed so much and a lot of our material now is online, primarily most of our auction catalogs. In this regard, we are asking the galleries to consider sending PDFs now. We want to make the material available remotely as much as we can.

This means that you must look at your collection from two perspectives: as a collection of objects and as a resource for the production of knowledge.

We do both because since we are the library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, we loan our books to exhibitions everywhere, including The Met exhibitions. So, on the one hand, our job is to have the books as objects and to keep them preserved and in excellent condition, on the other accessibility is as important, if not more.

Most objects in your collection relate to the art of the Americas and Western Europe. Could you tell me about some of your most important books relating to the art of Central and Eastern Europe?

Of course, we do have American and European resources, but we are a comprehensive art research library and with a broad selection of international publications. We do have a lot of important Czech publications, including periodicals, monographs, and exhibition catalogs. We also have a wonderful collection of Czech bindings that were published by Jan Otto, 36 books with linocut wrappers designed by designed by Czech artist Josef Čapek (1887–1945).

In terms of modern Viennese art, the collection that we have also reflects the time when styles like the Viennese Secession and French Art Nouveau were influencing Eastern European designs. My college Jared Ash, the Special Collections Librarian, specializes mainly in Eastern Europe. And he was precisely hired by Watson about 12 years ago to increase and enhance our holdings of books from this area. Since then, he has done incredible work.

How does the sociopolitical history of the modern era manifest itself in your collections? What can be observed?

Many books from our collection reflect sociopolitical history. For example, when I was at a book fair a few years ago, we acquired a trade catalog of women’s and men’s shoes from the Soviet Union. It was very interesting to us, and we purchased that publication as a representation of the fashion and social conditions of the Soviet period.

Of course, the exhibition Artist of the Holocaust tells another socio-political history. We also have a collection of over 900 American publishers’ bindings decade by decade. We observe that the bindings from the 1850s, which were made during the Civil War, are very exceptional; they suddenly became very plain and austere, with dark colors opposite from the more colorful bindings that came before and after. Another very important series we have is the large folio volumes from 1809 and 1828 from Napoleon’s expedition. These unique printings date from the period when Napoleon tried to conquer Egypt. Accompanying researchers and artists created engravings and etchings of what they saw.

We have initiated projects that reflect diverse cultures, nationalities, and origins. We received an important grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to acquire material that was concentrated on LatinX, Hispanic American, Asian American and Pacific Islander artists. In recent years, we have hired about seven library students to obtain hundreds of books in these areas. We are also studying the Jewish Diaspora and acquiring books in the Jewish Diaspora. Moreover, in 2021 we launched a project on gathering African American books from the 17th century and following decades. We have already collected thousands of publications in these areas.

Did the founders of the library plan to collect books from around the world?

The Library was founded at the same time as the Museum in the 1870s. Since the beginning, it aimed to represent global art. When we go back and look at our early acquisitions, we can already find books published all over the world. But I would say that in the last few years, since 2020, we have initiated projects to represent some groups even more. We also have a special Latin American initiative we have been working on since the mid-2000s; we acquired as much Latin American material as possible.

How do items in your collection reveal their individual international stories?

Sometimes it is incredible. For example, we have a book made of glass, a trade catalog of Saint Gobain, a very prominent glass company. They provided glass, for example for the mirrors at the Hall of Versailles or the Crystal Palace. We acquired their catalog dated, I think, 1890 to early 1900s, it is very heavy, and the pages are actual glass samples. They make noise as you peruse them! The relatively plain maroon cover has this great black lettering; the typography itself indicates its period. And the only way that we were able to date it is because there was a printed telephone number, the samples looked much older.

How did the prints you have on display in the Artists of the Holocaust exhibition find their way into your collection?

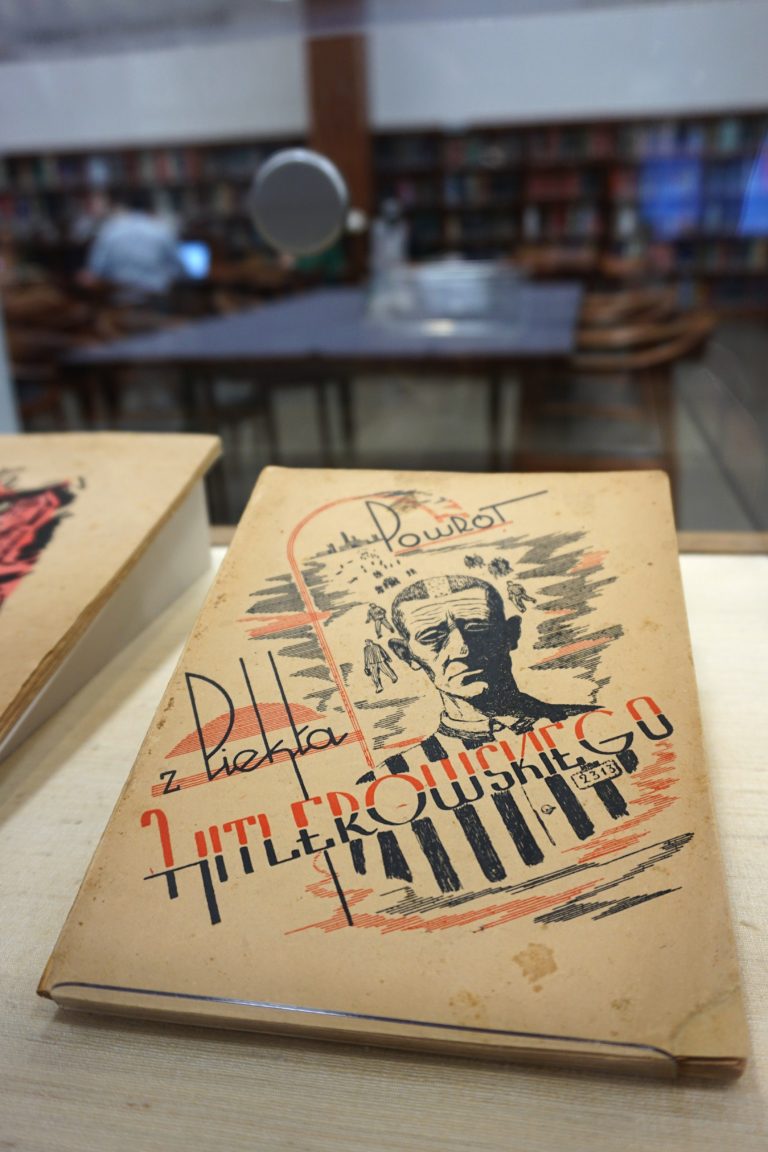

I recommend viewing the exhibition online, but I am happy to give a brief overview. We have been acquiring books on the Holocaust throughout. But it was in the last ten years that the Chief Librarian and I increased our focus in this area. And then we received two important gifts, including books on the Holocaust, one in 2017 from Judaic scholar and curator, the late Cissy Grossman, and one in 2020 from Tom Freudeheim, former director of the Baltimore Museum of Art. We knew it was very important to put them on display; we could not believe that we were able to acquire rare books from as early as 1944. So, in addition to later publications and exhibition catalogs, we have a core group of portfolios, memoirs, and exhibition catalogs published in the 1940s. We were going to display the material originally in 2022, right when the Russian aggression in Ukraine happened, so we decided to postpone it. And then, of course, none of us could have ever thought or knew what was going to happen, the current atrocities right now.

What made you choose these particular books for the presentation?

We wanted to show a selection out of our 450 publications on art in the Holocaust. As the Museum represents artists from all over the world and in all periods, we are representing art from this period, during the war. We hope that the exhibition will give voice to the artists and show how important books are to educate.

I have at home an album of drawings by an artist who survived the Holocaust. Some of these publications—testimonies—were recently presented at exhibitions in Poland. I noticed that they mostly were produced in very limited editions and printed on cheap, thin paper. I guess that, as a result, many did not survive.

One of the rarest books we have on display is by a Czech artist, Bohumil Stibor. These are ten woodcuts of his experience in concentration camps; only three copies are known worldwide, including ours. It is so important to share this material.

Finally, I would like to ask, what do you think the mission of American institutions should be in telling global stories?

Our mission as a library is to educate and to inform. And the museum’s mission is to enlighten, inspire, educate, and inform globally. These are all our shared stories. It is essential for us to learn about other cultures that we are not familiar with. Again, The Met has been doing this all along because it aims to be encyclopedic. Books are knowledge, as is art. is. That should be the mission, and it actually is our mission.

You certainly have much better access to resources that allow you to enhance and protect your collections.

We have an endowment, a budget, and a Friends group, The Friends of Thomas J. Watson Library, and other generous donors. Thanks to the Friends, we can continue to grow our acquisition of our special collections. For which we are so grateful. This is essential for us to keep building our collections of rare materials.

Holly Phillips is responsible for acquiring rare research material and overseeing the gifts program. She holds a BA in Art History from Barnard College, and an MA in Art History (specializing in nineteenth-century art) from Columbia University. She joined the staff of Watson Library in 1995. Holly works closely with the Arthur K. Chief Librarian, Kenneth Soehner and with Jared Ash, Florence and Herbert Irving Museum Librarian, Collection Development; building strong collections representing both broad areas of the fine and decorative arts as well as special focus areas including American publishers’ bindings and Judaica, most recently building an extensive collection of rare, retrospective and current material on Artists of the Holocaust. Holly has contributed numerous essays to the Library’s blog, In Circulation and she shares the collection with the public regularly by organizing exhibitions, presenting the material, and in and meetings with students and researchers. She recently curated Artists of the Holocaust: Portfolios, Exhibition Catalogs and Monographs in Watson Library, on view in Watson Library from April 18th, 2023 – January 9th, 2024.

Special thanks to Meryl Cates

The Thomas J. Watson Library – installation view