The Pleasure Of 90-Years-Old Before And After Pictures, Or The Rise Of Upcycling And Zoning In Liane Zimbler’s Living Space

Ladislav Jackson

In the 45th volume of the Innendekoration journal (1934), the well-known architect and interior designer Liane Zimbler published a modernization of a master bedroom in a prominent bourgeois apartment in Vienna. On a first glance, the project might look like a stylish interior commissioned by an upper class Viennese client with cash to spend. This desire for a fashionable interior where everything is selected and styled by the designer – even the client’s dressing gown – was mocked by Adolf Loos in his essay “The Poor Little Rich Man,” in which the client wanted the architect to “bring him art, art under his own roof, the money doesn´t matter!”[1] Creating a Gesamtkunstwerk, total work of art, by Otto Wagner and his pupils such as Josef Hoffmann was criticized by Loos on numerous occasions. For that reason, Loos’s own interior designs always had an eclectic nature and he substituted the aesthetics, the “total style,” with comfort.

Was the modernization of a bedroom from 1910, which had a very expensive furnishing in a very detailed, stylish design, ‒ at that point only 23 years old – this case, a vanity to show off a social status, or was it a necessity that would make the lives of the residents easier and indeed more modern? And does Zimbler’s project reflect her original thinking?

Liane Zimbler was an exceptional woman. She was born as Juliane Angela Fischer in a German-speaking Jewish family in Přerov, Czechia on May 31, 1892. She studied at the Realschule in Vienna and afterward, was granted status of an “exceptional student” at the Vienna School of Applied Arts (Kunstgewerbeschule) which was led by Alfred Roller between 1909 to 1934. Thanks to his predecessor, Felicien von Myrbach, its program was ruled by the Vienna Secession group: Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser and Oskar Kokoschka.[2]

Starting in 1908, Franz Čižek began to teach at the school and a younger generation of architects such as Josef Frank and Oskar Strnad became more pronounced at the school in the next two decades. Zimbler’s biographers are not sure whether Josef Hoffmann was her direct teacher, but she knew him either from the school or its close circles.[3] Zimbler got to know Hoffmann very well in 1920s, when she started to work for Wiener Werkstätte and, in 1925, she established a fashion branch of WW in Prague.[4] Hoffman’s way of thinking about a total interior design had a clear effect on Zimbler.[5]

However, she also adopted some of the principles represented by Frank and Strnad. Even though she had to obtain exceptional student status, Franz Čižek’s openness to bring up women to the field of architecture must also have been significant for Zimbler’s decision to remain in the male-dominated environment and pursue the career of an architect. Zimbler’s attandence between 1912‒1916 must have been a role model for the next generation of women who were admitted to the school, such as Margarette Schütte-Lihotzky, who started studying there in 1915, or Erika Giovanna Klien, who started in 1919.

Modernization of an older structure was Liane Zimbler’s first significant commission in 1922. A 1879 building, designed by Heinrich von Ferstel, was supposed to be adapted for a new owner: the changes to the building that were designed by Zimbler in the next two years were subtle, yet they transformed the usage of the building into a multifunctional, modern palace. First, Zimbler adapted the attic into three apartments, added one floor creating a roof garden with a fountain, then she put a glass roof over the courtyard and changed a mezzanine apartment into three smaller units. Liane Zimbler showed her very unique sense for preserving the original values of the older structure in question but at the same time she was able to improve the functionality for up-to-date requirements with minimal means.

This skill became very valuable to Zimbler when it came to interior design in 1930s. The commission to modernize the bedroom was clearly not just vanity, or a desire to be fashionable. Change of functions was encrypted in the task itself: the bedroom “had meanwhile become the main living room for the lady of the house, since the former drawing room had been converted into a children’s room. The room was not furnished practically enough for this multiple use. A special feature here is the further use and conversion of existing furniture.”[6]

The leading motif of designing the bedrooms in the 20th Century came to place here: Liane Zimbler had to find a solution as to how to combine more than one function/activity in a bedroom: living bedroom was born. Liane Zimbler refused to go in steps of a “stylish interior” which was represented by the Wagnerschule and especially Josef Hoffmann. She introduced upcycling and recycling to Viennese modernism: “The furniture is of good quality, so there is no need to replace it with new purchases. The wood was stripped, freshly stained and polished. Decorative elements on the furniture disappeared. The two existing cupboards were placed on the wall opposite the window and given a new division and elevation up to the ceiling. Inexpensive additions made of spruce wood were placed in front of an unused wallpaper door, in front of which a light silk curtain is drawn across the entire width of the room, the color of which is coordinated with the walls.”[7]

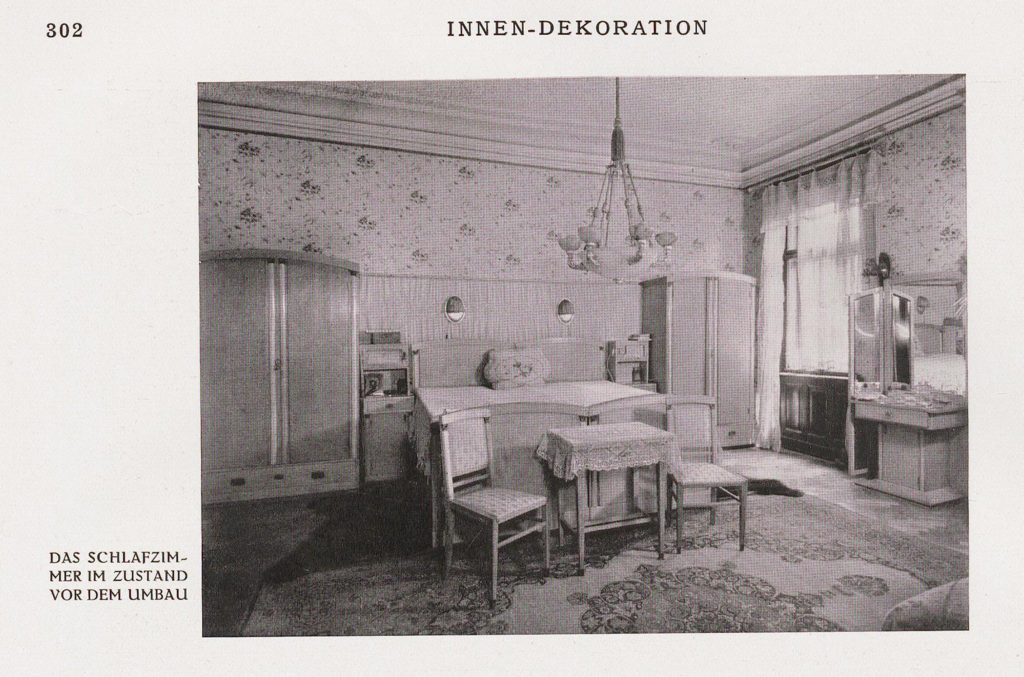

Zimbler provided in her short description published in Innendekoration a very lapidary comment: the old state of the bedroom was “aesthetically unsatisfactory, too little closet space, too many doors, no comfortable place to sit! The good quality of the woodwork suggested a remodeling of the furniture.”[8]

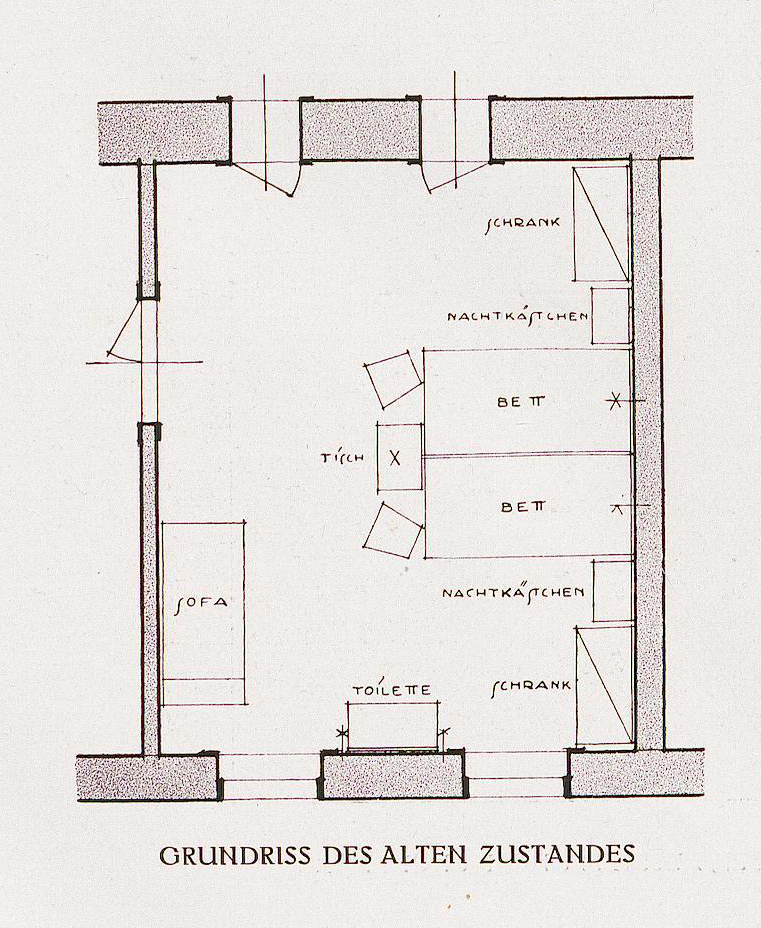

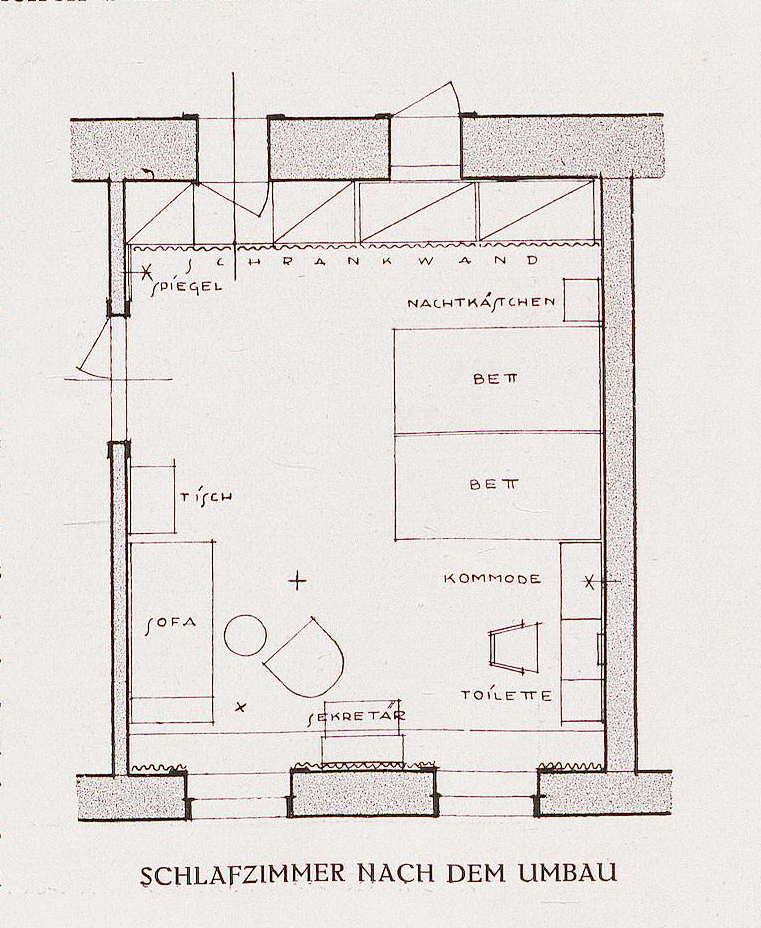

The original room was set up by a monstrous symmetrical compound including a double bed, bed stands and two massive wardrobes. There was a small sitting area in front of the bed’s headboard. There was a toilet stand between the windows and a small sofa behind the entrance door. There were two other entrance doors to the room in the side wall. Zimbler decided to blind the two side doors when she placed a built-in closet all across the side wall: one door was totally blinded and the other door lead through one segment of the closet. She moved the bed closer to the closet wall which made more space in the window area. Next to the bed she placed a large toilet stand with a chair, she moved the sitting area to the “window corner area” where the sofa remained. The sofa had two purposes now: as a sitting sofa and as a temporary and/or a day bed.

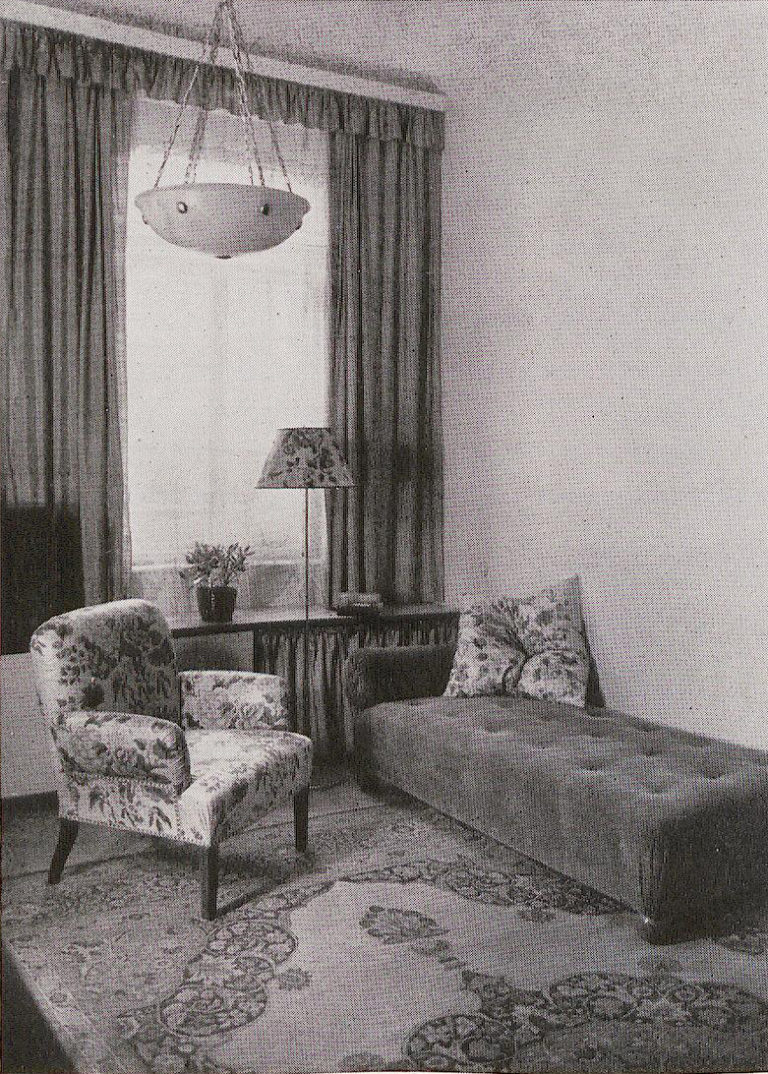

The upcycling of the furniture did not only involve stripping the decorative elements off, Liane Zimbler decided to change the tone of the furniture: “The unsightly ash has been stripped and stained and polished to a warm cherry tone,” she wrote. Although she removed the floral ornamental wallpapers and heavy curtains, which was supposed to make the room more spacious, she did not follow the reductionist doctrine of international modernists.

To some extent she was at the same time aware of the comfort qualities, promoted by Loos, and the furniture took on an eclectic touch: she added a floral, low, thick padded armchair, typical for Loos’s late interiors. The window corner area became a separate zone for dayusage. Floral ornaments from the armchair were repeated on a large pillow on the sofa and on a lamp shade, all the furniture was placed on a big oriental rug with ornamental pattern that was originally in the center of the room. The upcycling element of Zimbler’s design was not limited just to furniture, but also glass particles. “The narrow mirror was taken from the side of the old dressing table, and the small frame for the perfume bottles was made from the lower part of the pharmacy attachment.”[9]

Zimbler was not only able to organically combine four different functions in the room, while it originally had two, she also created a visual distinction between them (minimal design of the sleeping area and storage spaces, comfortable design for the toilet area and the window corner for the day activities).

As Christina Gräwe suggests in her on-line published biography of Zimbler, Liane Zimbler continued to modernize, renovate, reconstruct and remodel older interiors throughout the entire 1930s. She was able to subtly create new functional spaces, such as corners and zones, out of no longer functional rooms, such as entrance halls of bourgeois pre-war apartments. In 1932, she turned a long, narrow hallway in a Viennese apartment into an extended living space. Zimbler didn’t need massive separation panels or pieces of furniture, she created smaller “areas”, functional zones with usage of minimal furnishing: sophisticated placing of a rug, hanging a curtain, designing a subtle dresser or just simply changing the visual style of a new zone, as she did in the Viennese bedroom.

As a woman, Zimbler also was able to actually see the woman in the domestic space as a subject, not a “decorative” object like most of her male colleagues. She knew what it meant to move around the house on an everyday basis, not on a representative, festive moving “paths” like in Frank’s and Loos’s homes. She understood what it meant when a woman’s drawing room turns into a children’s room. It was not just the design of the children’s room, that needed to be done, but the architect needed to create another “room of one’s own” for the mother within the domestic interior: in both material and a symbolic way.

Liane Zimbler’s Viennese designs were not experimental in the way the entire domestic space and it’s volume and movement is organized, as suggested by Christopher Long when he discussed the specific inventions of Viennese modernists such as Loos, Frank and Strnad in his book The New Space, where neither Zimbler nor Klien are mentioned at all, Schütte-Lihotzky once, only as a witness of Strnad’s accomplishments[10]. Zimbler’s legacy is different, she tried to reorganize the domestic interior according to modernist values with as little means, products and waste, as necessary. Zimbler took these approaches and methods with her when she emigrated to the United States following Nazi annexation of Austria on March 13, 1938.

Historically, I believe that we need to consider these rather subtle inventions by Viennese modernists who migrated to the United States from Austria more seriously when we look at the rise of California mid-century modernism, its principles, aesthetics, and materiality. And, on top of that, in the 21st Century, facing the impacts of a climate catastrophe, I believe that we can learn from Zimbler more than we can learn from all of her Viennese male colleagues combined. When we look at attractive “before” and “after” images in life style magazines, next to the questions of how much new light was allowed in the living space, or how much of the old junk they got rid of, we need to add to our consideration also the questions of what was the carbon footprint of the whole project, how much of the original material did they upcycle and how much new stuff had to be manufactured to achieve the effect.

[1] August Sarnitz (ed.), Adolf Loos, 1870-1933, Architect, Cultural Critic, Dandy, London; New York, 2003, pp. 18‒21, quoted p. 18

[2] See chapter “Die Einfallenden” – Josef Hoffmann und die Kunstgewerbeschule in Iris Meder, Offene Welten: Die Wiener Schule im Einfamilienhausbau 1910‒1938, dissertation thesis, Institut für Kunstgeschichte der Universität Stuttgart, 2004, pp. 34‒41

[3] According to her autobiography from 1973, see Christina Gräwe; Thomas Spier, Liane Zimbler, http://www.liane-zimbler.de/text/kapitel_2_1_1/frameset_text.htm

[4] See Miroslav Ambroz, Aleš Filip, Rainald Franz et al., Vídeňská secese a moderna (1900—1925), Brno 2005, p. 155

[5] As Gräve suggests: his „influence can be seen in Zimbler’s later office organization and realized designs that may have corresponded to the convictions he conveyed.” Christina Gräwe; Thomas Spier, Liane Zimbler, http://www.liane-zimbler.de/text/kapitel_2_1_1/frameset_text.htm

[6] Christina Gräwe; Thomas Spier, Liane Zimbler, http://www.liane-zimbler.de/ text/kapitel_2_2_3/frameset_text.htm

[7] Christina Gräwe; Thomas Spier, Liane Zimbler, http://www.liane-zimbler.de/ text/kapitel_2_2_3/frameset_text.htm

[8] Liane Zimbler, »Elegantes Schlafzimmer« von 1910 ‒ Modernisiert, Innendekoration, 1934, vol. 45, pp. 302‒303, quoted p. 302

[9] Liane Zimbler, »Elegantes Schlafzimmer« von 1910 ‒ Modernisiert, Innendekoration, 1934, vol. 45, p. 302‒303, quoted p. 302

[10] See Christopher Long, The New Space: Movement and Experience in Viennese Modern Architecture, New Haven, 2016