Cartoons and dancing poetry between Vienna and New York:

retracing the transatlantic career(s) of Lisl Weil

Julia Secklehner

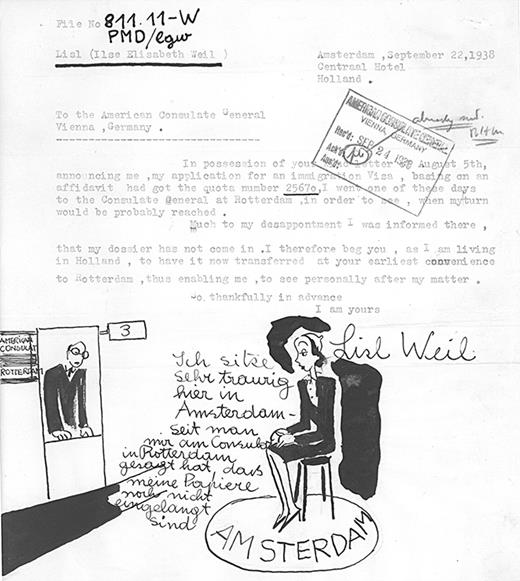

“Lisl Weil (previously illustrator for Die Bühne), Vienna, now reliably in New York” – With this short announcement, the Brussels-based emigre magazine Danubian-Echo introduces the Viennese migrant Lisl Weil in its 1940 column “Who is where”, which aimed to reconnect friends and families torn apart by war and persecution.[1] We do not know who searched for Weil, nor if they ever found her. Instead of a reunion, the entry represents a rupture: it is the last time that Weil, then a thirty-year old cosmopolite and successful cartoonist for various Viennese newspapers and magazines, effectively disappeared from the Austrian press. Letters indicate that her journey after forced emigration in 1938 first took her to Holland. A letter by Weil from September 1938 locates her in Rotterdam, waiting for her visa to the United States. Significantly, the letter was more than an ordinary inquiry. It belongs to a series of so-called “freak letters” collected by American diplomat Leland Burnette Morris, who would save mail by visa applicants that were specially presented to gain attention in an overflowing system of applications.[2] In Weil’s case, the letter not only caught Morris’ attention, but also shows her line of work at a moment in time when emigration forced her to recalibrate her career.

The letter is decorated with a naïve self-portrait caricature at the centre, waiting in an office. An accompanying text in German reads “I sit very sadly in Amsterdam, since I was told at the Consulate in Rotterdam that my papers have not yet arrived”.[3]

The sketch is drawn quickly across the formal inquiry, adding a humorous note to a desperate situation. Morris noted that he found the drawing “quite amusing”, while historian Melissa Jane Taylor has suggested that the letter „appears to have been written by a child, although none of the writers gave their age“.[4] Even though both of these descriptions are not quite correct in that the cartoon was to emphasize its author’s precarious situation until receipt of her visa, and it was produced by a woman rather than a child, they nonetheless encapsulate the two most significant aspects of Weil’s work: humorous popular cartooning, which was Weil‘s main line of work until 1938, and educational entertainment for children, in which she began to specialize in the years following her arrival to the United States in 1939. Taking this as a point of departure, this essay introduces the different aspects of Weil’s career on both sides of the Atlantic and shows how her multi-valent practice in Vienna set her up for a new career in the United States after emigration.

Weil was born in Vienna in 1910 under the name of Ilse Elisabeth Weisz. She took on the name Weil with her adoption by the businessman Isidor Weil in 1923. From the age of nine, Weil began to attend Franz Čižek’s youth art classes at the Academy of Applied Arts in Vienna, after which she studied at the Academy from 1926 to 1930.[5] In addition to her artistic education, music and dance also played an important role in Weil‘s life early on, and she attended ballet classes by the famous Viennese expressionist dancer Grete Wiesenthal as a teenager.[6] Weil‘s comprehensive schooling in art and design set her in midst central cultural institutions of interwar Vienna and shows the many options open to young women seeking to pursue creative professions at the time. Embracing both a rising fashion of alpine culture in Austria, as well as a cosmopolitan lifestyle, with Paris becoming a frequently cited reference in the artist’s illustrations, Weil‘s career at the time was in many ways typical for that of young (Jewish) Austrian women, who played with the registers of modernity and tradition both in their multivalent creative work.[7]

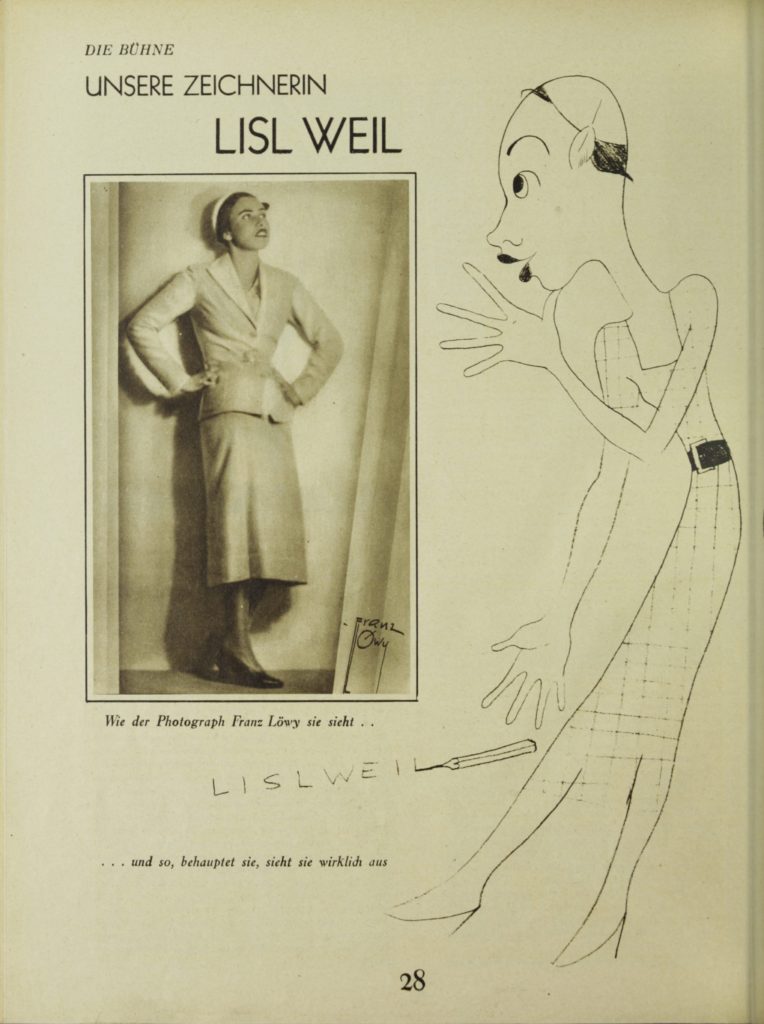

By the mid-1930s, Weil worked as a stage decorator including productios in Vienna‘s Josefstädter Theatre.[8] More importantly, however, was her career as a newspaper illustrator and cartoonist, which she already began as a teenager. Over the course of the 1930s, she contributed to a range of different Viennese magazines and newspapers, including Die Stunde, Das interessante Blatt, and Götz von Berlichingen. The most important publication for her career was, no doubt, the society magazine Die Bühne, for which she regularly produced cartoons and illustrations that provided humorous commentary on the lives of Vienna‘s high society.

A main concern in Weil‘s drawings throughout were the lives of modern women. A 1930 sojourn in Paris, for example, was serialised in Die Bühne under the heading “Lisl Weil’s Picture Broadsheet of Paris” (“Bilderbogen von Lisl Weil, Paris”). In it, Weil shows a series of cartoons under a joint heading, such as “autumn hunt” in November 1930, in which women chase for the perfect figure, love, money, but also bedbugs in a rundown little Paris apartment.[9]

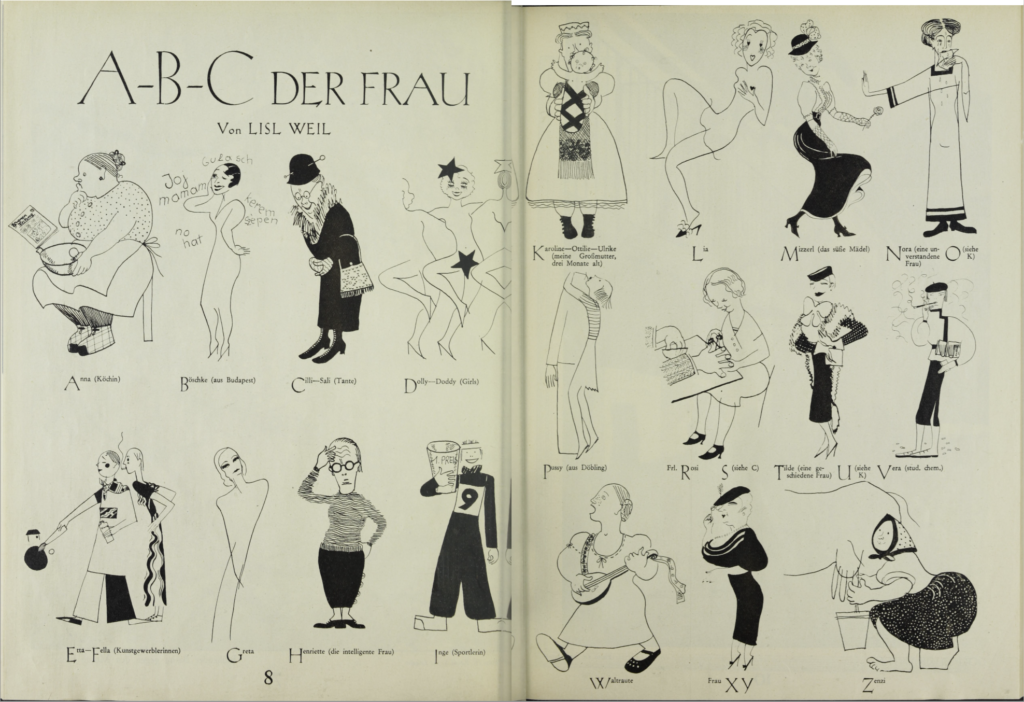

A particularly entertaining summary of Weil‘s repertoire of modern women is the “A-B-C of Women”, published in Die Bühne in 1933: each letter of the alphabet is represented by a different “type” of modern femininity, starting with Anna, the chef, and ending with the milkmaid Zenzi.[10]

In between, there are showgirls (Dolly and Doddy), craftswomen (Etta and Fella), sportswomen (Inge), the divorcee Tilde and the chemistry student Vera. Including Czech and Hungarian names, as well as women from different social classes, Weil‘s alphabet shows a plethora of different characters that she would have encountered on the streets of Vienna and the Austrian countryside. Indeed, even though most of her characters are quite clearly at home in Vienna, such as Mizzerl, the famous “sweet Viennese girl” presentation of a prostitute, written about by Arthur Schnitzler in his 1908 play Comtesse Mizzi, others, such as Zenzi, are located in the countryside.[11] The inclusion of rural characters relates to Weil’s mobility between Vienna and rural Austria. They specifically appear during summer holidays summer holidays (“Sommerfrische”) in the Salzkammergut Lake District, where she was a member of the Zinkenbach painter’s colony on lake Wolfgang.[12]

Her illustrations for Die Bühne on the occasion of the close-by Salzburg Festival are a striking mixture of naïve forms and simple lines, paired with a sense of light-hearted humour. “Interview with a Dirndl Dress”, for example, in which a Dirndl (a traditional folk dress) in a Salzburg shop window muses about its importance in modern fashion. “Playing farmer’s wife and farmer is ‘le plus chic’ at the moment, I mean, ‘up do (sic) date’!”[13] Telling readers about potential French and Japanese customers, the dress wishes to be bought by an Englishwoman: while it is born in Salzburg, it feels at home in the world. In an extended sense, this strong local Austrian flavor, paired with a cosmopolitan lifestyle is what defines Weil’s work throughout the 1930s – most visible in her cartoons, but also in other illustration projects, including the cover for music sheets. In other words, a passion for music and humorous drawing, playing with elements of Austrian folk culture while deeply embedded in the life of a modern socialite, manifested Weil’s presence in the interwar press as one of Vienna’s first female cartoonists. With the annexation of Austria to the Third Reich in March 1938, however, Weil’s unusual career came to a quick end. Together with her sister and her nephew, she was forced to emigrate, waiting in Holland to receive a visa for the United States. This forced emigration marks not only a personal rupture in her biography: her pre-war work has almost wholly been forgotten, even though her many cartoons and illustrations offer refreshing insights into the ways a young female artist perceived life in Viennese society between the wars. In this regard, Weil’s drawings might be compared to the “Kleßheimer Sendbote” cartoons of Erika Giovanna Klien (1927), also a student of Čižek. However, while Klien’s cartoons were in the form of private letters to friends, Weil’s were printed regularly in the press, this representing an intrinsic part of popular Viennese culture. Not least, the playful approach she took in these illustrations, always pairing an acute sense of observation with joyful imagery, would remain a significant aspect of her work in her “second career” in the United States.

Arriving in New York in 1939, Weil initially worked as a decorator for shop windows for Lanz, a popular Salzburg-based business specializing in fashion inspired by traditional Austrian costumes, which had recently opened branches in Los Angles and New York.[14] At this time, Weil also married Julius Marx and became an American citizen. Like many artist-migrants who had had built careers in Europe, Weil’s professional life suffered from her forced move into exile and her profession as a cartoonist with intimate knowledge of her immediate (Austrian) environment had to be recalibrated to a new life in the United States. In Weil’s case, this meant a reorientation towards new audiences, whom she could transmit her interest in music and drawing, as well as her knowledge of life ‘elsewhere’: children.

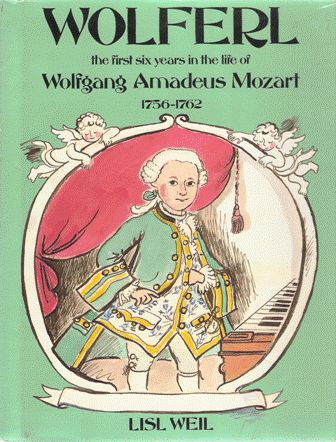

In 1946, Weil illustrated her first children’s book, Doll House, written by Marion Moss, followed by Jacoble tells the truth (1946), which Weil both wrote and illustrated. Over the course of the next decades, children’s book became the artist’s main line of work, building on her interest in music and different cultures as recurring themes. One of her most popular books was a biography of the Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1762), Wolferl. The First Six Years in the Life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1991), for example, and she wrote and published a picture book of the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana’s opera The Bartered Bride, as well as of Gioachino Rossini’s The Magic Toyshop in collaboration with the Lincoln Centre.[15]

In all these projects, Weil emphasized a playful, bright visual language, which strongly resembled her cartoons for Viennese magazines in the 1930s. However, rather than entertaining adult audiences, they put children’s education in focus, introducing different cultures to young American readers.

Aside from book publications, Weil’s most successful venture was a television show, produced by Weston Woods, a production company known for its creative approach to children’s visual education. In The Sorcerer‘s Apprentice (1962) she collaborated with the the Little Orchestra Society, an American orchestra founded by the conductor Thomas Scherman in 1947. While the music was playing, Weil made live drawings from The Sorcerer’s Apprentice with charcoal on a large white canvas, combining her practice in expressionist dance with illustration. In the 1960s, too, she developed a series of educational sound film strips, titled “Children of other Lands”, described by the National Leadership Institute for Teacher and Early Childhood Education as “a highly recommended social studies series”, comprising of four stories about the lives of children in different countries and social settings, including that of an Austrian boy, working in his grandfather’s inn.[16] Her children’s programs were performed live across the United States for over thirty years, including fixtures such as the Lincoln center, where she would decorate largescale canvases during her performances.

Looking back at Weil’s humorous illustrations from the 1930s, her playful approach to Austrian alpine culture in relation to the Salzburg Festival and, as well as her caricatures of modern women’s lives, her second career in the United States indicates a careful reframing of her core practice for new audiences. Despite her successful decade-long career in the United States, Weil’s work has almost been forgotten in Austria and it was not until 2006 that one of her books – Wolferl – was first translated into German. At the same time, the beginnings of her career in Austria are only rarely brought in relation with her later work: the University of Minnesota, which hosts Weil’s archive from the 1960s onwards, predominantly focuses on her work as an author and illustrator of children’s books, for example.[17] Drawn together, however, Weil’s biography brings together the career of a multivalent artist, who consistently reinvented herself. The many different stages of her training in interwar Vienna, including dance, drawing and stage design, not only led to her position as one of Vienna’s first regular female cartoonists, it also set her up for a profession in the United States in which her playful style was put to new uses and formed the basis for a wholly new career.

A comprehensive bibliography of Weil’s children’s book can be found below:

https://web.archive.org/web/20140803201200/http://www.picturebookcottage.com/index_files/Page680.htm

[1] “Wer ist wo?“, Donau Echo, 1 March 1940, 4.

[2] Melissa Jane Taylor, “Diplomats in Turmoil: Creating a Middle Ground in Post-Anschluss Austria”, Diplomatic History, Volume 32, Issue 5, November 2008, 831–832. https://academic.oup.com/dh/article/32/5/811/397378

[3] Lisl Weil to American Consulate General, Vienna, Germany, 22 September 1938, unnumbered, but attached to letter, 811.111 Quota 62/619. Translation from Melissa Jane Taylor, “Diplomats in Turmoil”, 832.

[4] Melissa Jane Taylor, “Diplomats in Turmoil”, 832.

[5] “Lisl Weil”, Museum Zinkenbacher Malerkolonie, https://www.malerkolonie.at/lisl-weil/ .

[6] “Weil, Lisl”, biografiA, http://biografia.sabiado.at/weil-lisl/ .

[7] See Sabine Fellner and Andrea Winklbauer, Die bessere Hälfte. Jüdische Künstlerinnen bis 1938, Vienna: Metro-Verlag, 2016. Megan Brandow-Faller, The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy, University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania University Press, 2020. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Anne-Katrin Rossberg and Elisabeth Schmuttermeier, eds. Die Frauen der Wiener Werkstätte / Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte, Basel: Birkhäuser, 2020.

[8] “Ein Festsonntag in Baden”, Neue Freie Presse, 30 July 1928, 4. “Jossefstädter Theater”, Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 11 April 1936, 14.

[9] “Herbstjagden. Bilderbogen von Lisl Weil, Paris”, Die Bühne, 291 (1930), 39.

[10] Lisl Weil, “A-B-C der Frau”, Die Bühne 347 (1933), 10-11.

[11] Arthus Schnitzler, Komtesse Mizzi oder Der Familientag: Komödie in einem Akt, Berlin: Hofenberg, 2013 (1908).

[12] Bernhard Barta, Das Malschiff, Österreichische Künstlerkreise der Zwischenkriegszeit, Vienna: Edition Schütz, 2007.

[13] Lisl Weil, “Interview mit einem ‚Dirndl‘-Kleid“, Die Bühne, 453 (1937), 50.

[14] “Lisl Weil”, Museum Zinkenbacher Malerkolonie, https://www.malerkolonie.at/lisl-weil/. “Geschichte”, Lanz, http://www.lanztrachten.at/lt/geschichte/ .

[15] David Sterritt, “New York’s Lincoln Center is humming”, Christian Science Monitor, 24 December 1982, https://www.csmonitor.com/1982/1224/122401.html .

[16] Harry A. Johnson, “Multimedia Materials for Teaching Young Children: A Bibliography of Multi-Cultural Resources”, March 1972, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED088578.pdf ; “’Children’s Sketch Book’ and Lisl Weil”, Children’s Media Archive, http://childrensmediaarchive.blogspot.com/2018/07/childrens-sketch-book-and-lisl-weil.html .

[17] “Lisl Weil Papers”, The Children’s Literature Research Collections, University of Minnesota, https://archives.lib.umn.edu/repositories/4/resources/2565 .