From Secessionist Vienna to Postwar America:

Emmy Zweybrück, Franz Cizek and the Cult of Child Creativity

Megan Brandow-Faller

The cult of child creativity taking root in postwar America—or notions that all children are inherently creative with unique access to imaginative and expressive powers—remains ubiquitous in contemporary American society, as manifested in elementary and preschool curricula, a pervasive “do-it-yourself” culture for artistic practice in the home, and a multi-billion dollar art supply industry. But despite their importance to the postwar American political consciousness, rarely are such discourses on child creativity connected to their intellectual roots in Secessionist Vienna. Based in Vienna until after the Anschluss, Zweybrück possessed a preeminent international reputation as an art educator associated with the permissive methods of free expression linked to Klimt Group member Franz Čižek (with whom she studied and apprenticed). Publishing widely on contemporary handcraft, Zweybrück ran applied-arts workshops specializing in textiles, embroidery, toys and book illustration, in tandem with her progressive craft school for girls (opening in 1915), which, in turn, cultivated a seemingly “naïve” design language inspired by folk art and children’s drawings. Attracting the attention of American visitors, Zweybrück offered regular lecture tours and seminars in the United States throughout the 1930s. Publications like The Stencil Book (1935) and Hands At Work (1942) encouraged teachers to free the spark of creative genius slumbering in every child, ideas also spread through her work as artistic director of the American Crayon Company and editorship of its promotional journal, Everyday Art. So renown was Zweybrück’s international reputation as an craftswoman, designer and art pedagogue that she was honored with a retrospective exhibition (Fig1) at the Vienna Secession in Summer 1955, curated by her close associate, Josef Hoffmann.

While Zweybrück is often compared to familiar male touchstones like Čižek, Zweybrück was entirely unique in her roles in marketing and commodifying child creativity and progressive modernist design. Interwoven with subtle product endorsements for American Crayon Company products (only use ‘E-Z Cut Transparent Stencil Paper’ etc.), Zweybrück penned meticulous, step-by-step instructions for handcraft projects in a buoyant sunshine-y style intended to encourage amateur makers to create handmade table linens, wall hangings, greeting cards and prints with ease. Readers were greeted with inviting headings such as YOU CAN DO CROSS-STITCH EMBROIDERY OR STENCILING IS EASY TO DO. Such instructional prose, paired with new product lines, beg the question of whether amateur hobbyists truly intended to undertake Zweybrück’s complex projects, or merely lived vicariously through a fiction of self-directed improvement and perfectionism not unlike what critics have observed apropos the Martha Stewart phenomenon.

* * * * *

Zweybrück’s postwar American legacy was rooted in interwar Vienna, widely likened to a mecca of progressive art education. Droves of English and American art teachers, critics and artists flooded the city to witness firsthand the progressive methods of Franz Cizek, Emmy Zweybrück and others, who, by the early 1920, carried preeminent international reputations and ran special guest courses to train art teachers. Cizek’s Anglo-American influence was anchored through the English-language translation (1927) of his manual on paper-cutting (originally published 1914) and the Cizek School’s travelling exhibition (originating at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in December 1923 and touring through Brooklyn, Baltimore, Washington, Chicago, Los Angeles and San Francisco). First touring through England (1921-1923), Cizek’s American exhibition catapulted him to international fame to the extent that he remembered an American “Völkerwanderung” (great migration) and how attending students were dwarfed by American visitors (sometimes 3:1).[1]

Cizek’s fascination with the raw, spontaneous power of children’s drawings dated to his own youth, when he remembered following his 3-year-old sister’s first attempts at drawing. The son of a secondary drawing instructor from Leitmeritz Bohemia, Cizek moved to Vienna in 1885 to study painting at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts, at which point he rented a room from a carpenter. In his rented quarters, which received superb northern light, the young academy student set up a makeshift studio, dominated by a huge wooden plank formerly used for cavalry riding exercises. In the afternoons, as his Academy studies only occupied him in the mornings, young boys from the neighborhood began to gather and scribble “all sorts of riotous things.”[2] The budding artist admitted to studying these scribbles first out of sheer curiosity but later with the very serious conviction that these drawings seemed to follow eternal laws of form across time and space and manifested children’s emotional and spiritual states. As he remembered:

At that time ‘the art of the child,’ as it is called today, did not exist. Children’s scribbles were not tolerated and, in fact, punished. In families it [children’s scribbles] became the bane of the housewives; fathers and teachers found steel wool the most suitable material to do away with this nuisance. So many people (especially teachers) took me as a fool for engaging with these scribbles as if they were things to be taken seriously.[3]

First rediscovered in the seminal 1985 Wien Museum retrospective, Cizek’s reputation as a progressive pedagogue now stands preeminent in the annals of Viennese artistic and cultural history.

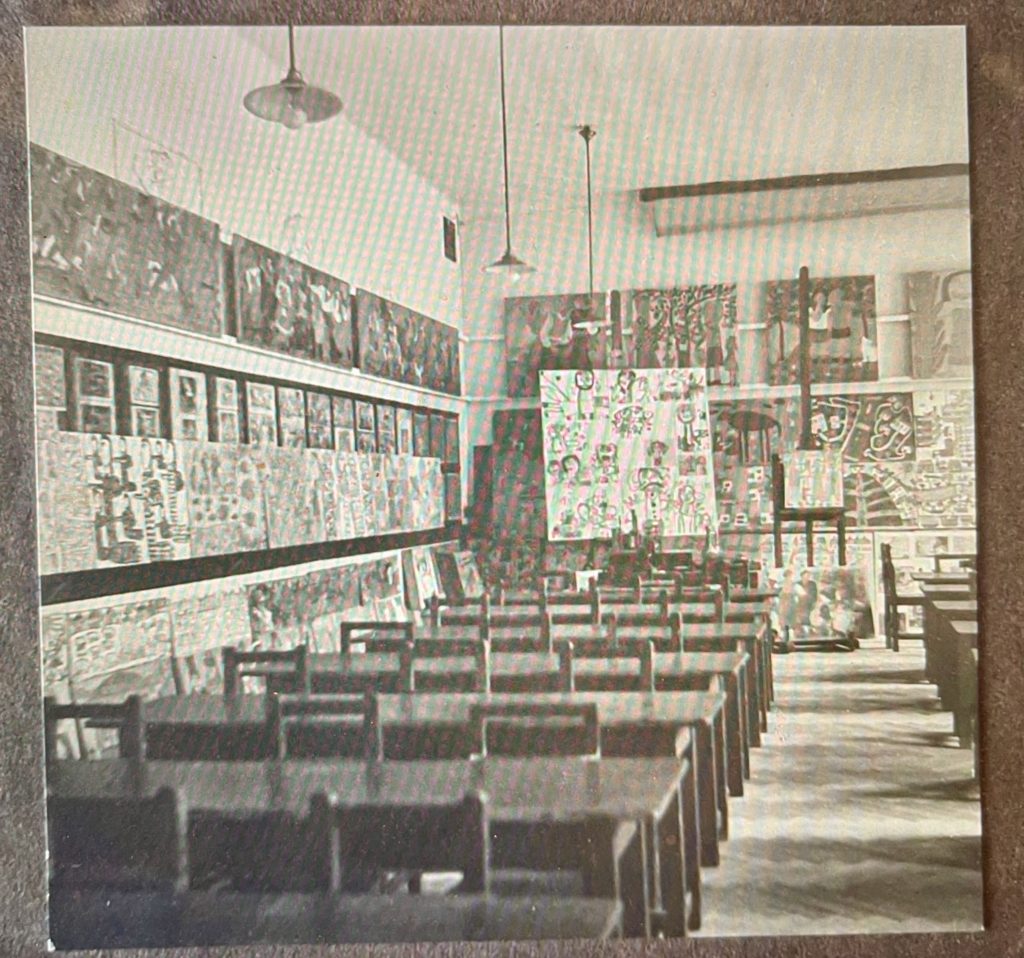

In his famous Youth Art Classes (Fig 2), operated out of the Austrian School of Applied Arts from 1904 onwards, Cižek shunned conventional methods of art instruction privileging skill, and technical accuracy. Seeking to unlock the inborn creative drives he believed resided in every child, the pedagogue encouraged pupils to release inner experiences through free choice of handcraft media. A critical part of his pedagogy was his notion that children should be sheltered from the conventions of adult art, or the corrupting influence of books, journals, and museums. In Čížek’s classroom (Fig 2), children were left to teach themselves, supposedly uninfluenced by the teacher. The course’s aim was patently non-vocational— to broadly nourish children’s creativity without a specific professional trajectory—and was popular among patrons of Klimt and the Wiener Werkstätte who supported the Secessionist ‘art for the child’ movement. Cizek’s manual on paper-cutting methods for children not only inspired fellow pedagogues, but directly influenced contemporary design and art, including the childlike aesthetic of early Expressionism, as I covered at length in my 2020 monograph The Female Secession.

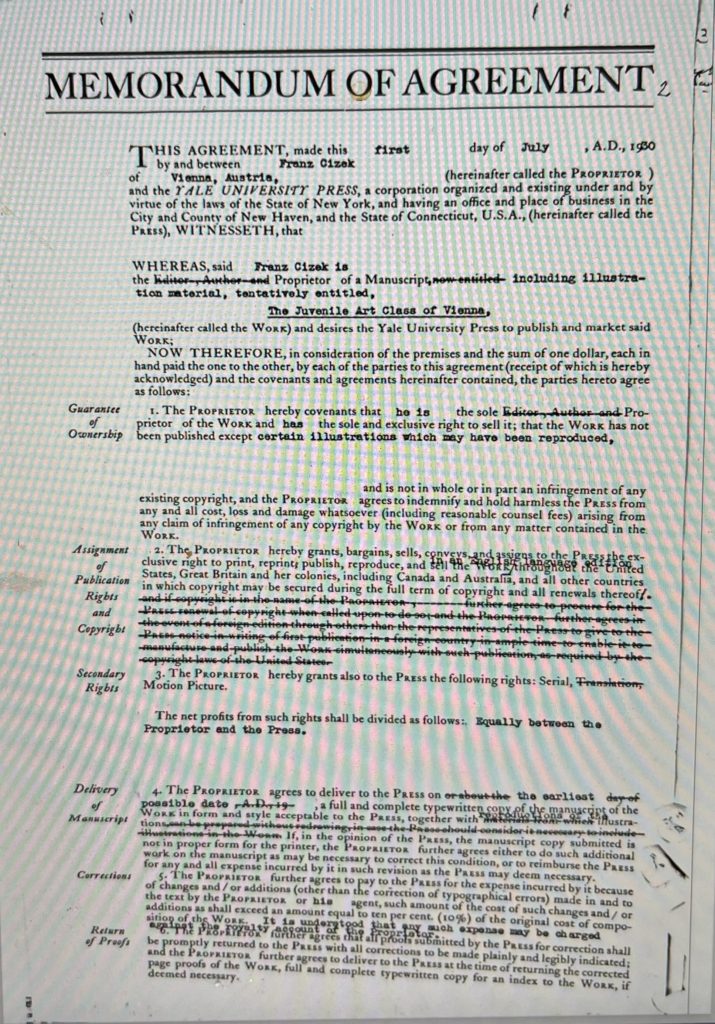

Yet other aspects of Cizek’s legacy await rediscovery. Large expanses of the Cizek Nachlass (now housed in the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus) document the involute paper trail surrounding Cizek’s unfinished English-language manuscript for Yale University Press, which would have brought the pedagogue unparalleled acclaim in the English-language world. Extensive correspondence between Cizek, his American publisher and editors, as well as non-profit organizations financing the illustration program, demonstrate that the project was much more than a pipe dream but was commissioned and under contract (Fig 3).

Yet unexpected complications ultimately derailed the project and prevented its publication, despite efforts to bring it to completion after the pedagogue’s death in 1946.

Cizek’s American book project was originally conceived to be a picture album of the most striking works of the Jugendkunstklassen. But the demand arose from American art educators that the work be of a more theoretical, authoritative nature, addressing the organic growth of children’s creativity and eternally valid laws of visual creativity. As such, the book project had to be re-conceptualized from the ground up and previously gathered materials scrapped. Ultimately, the costly image program, coupled with the economic crisis of the 1930s, made the Cizek project untenable. Per se the terms of his contract, the author had to subsidize the image program and costly preparation of the lithographic plates both personally and through private donations, including generous grants from the International Society of Friends, a charitable organization facilitating communications with the press. But the ripple effects of the economic crisis—the loss of private grants; Cizek’s 1934 retirement (whereby his income sank by 2/5th); and the plummeting value of the Schilling—made the completion of book project impossible. Ultimately, Cizek’s Anglo-American reputation would be sealed through English-language translations of his pedagogical manuals and the writings of his followers.

******

Cizek’s slightly younger counterpart, Emmy Zweybrück, has often been understood—albeit incorrectly—in the shadow of more famous male contemporaries like Cizek or Hoffmann. Zweybrück shared with Cizek common emphases on expressing feelings, thoughts and emotions through free choice of handcraft media and permissive instructional methods. As writer Georg von Terramare encapsulated her school’s philosophies, “[c]hildren create freely from within themselves and should give thoughts and feelings personal expression, recording in a variety of media….everything experienced and seen.”[4] Zweybrück likewise de-emphasized traditional teaching methods in favor of students’ direct experimentation in handcraft materials, foregoing preliminary drafting on paper. As she held in her best-selling ‘DIY’ craft manual Hands at Work (1946), a work published and promoted by the ACC, “Everybody who works with color should experiment with his materials like a violinist uses his bow.”[5] Like Cizek, who disdained naturalistic copying and encouraged students to draw from memory, Zweybrück emphasized that applied design was “not simply a copy of nature” but should attempt to capture the rhythm or feeling of an object in a stylized or abstracted way rather than offer literal depictions thereof.[6] Both children and adult amateurs were to find inspiration in the ‘primitive’—and simultaneously modernist—visual qualities of folk art when decorating the world around them. As she instructed readers of The Stencil Book (1935), “[l]ike those peasant motifs, our designs should represent the objects stripped of all accessory details, in…a simplified manner.”[7]

Zweybrück’s lifelong interest in folk art—a critical source of inspiration for her workshops—reveals another point of overlap with, but likewise departure from, Cizek: the positive conflation of untrained children’s art with the art of so-called ‘primitive’ peoples from tribal folk cultures and potential of both categories as rejuvenating sources for contemporary art and design. While Cizek sublimated his painting career to teaching, Zweybrück’s prolific work in industrial and applied design was animated by a sustained engagement with folk art, which she collected and displayed in her school. Zweybrück readily admitted how her initial fascination with European folk art (including toys, painted furniture and religious objects) gave way to a freer style informed by Native American and Mexican objects after her emigration to America. However, in extending her appreciation of ‘primitive’ outsider art to the art of untrained amateurs, Zweybrück’s attitudes towards primitivism were more complicated than Cizek’s, who never broached the topic of the untrained. In her popular instructional writing, Zweybrück valorized the lack of formal training among adult hobbyists, summoning them to harness their unspoiled freshness much like the supposed “simplicity and naïveté” of folk artists.[8] As she advised: “[p]eople who are without art training should not be afraid of drawing because most of the time their motifs are even stronger and have more charm because they do not try to imitate nature.”[9] Unlike Cizek, whose experience with older pupils was limited to the high-school-aged students in his Ornamental Studies Course, much of Zweybrück’s career was dedicated to teaching adult amateurs, relating to her institute’s differential goals. Furthermore, while Čižek taught male and female students ages 4-14, Zweybrück’s school was only open to girls and was equipped with several divisions: 1) seasonal courses for very young children 2) a general division for girls not intending to pursue art as a vocation 3) a separate division for high-school aged pupils focused on professional handcraft training in preparation for guild examinations. In the latter regard, Zweybrück never rejected vocational training in the wholesale way that Cizek did even as her schools synthesized “the general humanistic training of the pupil” with vocational-professional goals.[10] As Terramare observed, a minority of “truly artistically gifted and talented” pupils were recruited for the Zweybrück Workshops, which specialized in embroidery, textiles, toymaking and interior design, where they found “encouragement and stimulation” through commissions, competitions, and the bi-annual school exhibitions open to all students. Such linkages between school and workshop, whereby successful school graduates went on to design for the workshop or teach in the school, paralleled the close institutional linkages between the Secession/Wiener Werkstätte/Kunstgewerbeschule, the latter of which Moser and Hoffmann used as a talent pool for the Werkstätte. Yet the Zweybrück Workshops were distinct from the WW in representing a distinctly female form of entrepreneurship: the firm was led by women; staffed by female school graduates; and focused on matrilineal forms of artistic transmission.

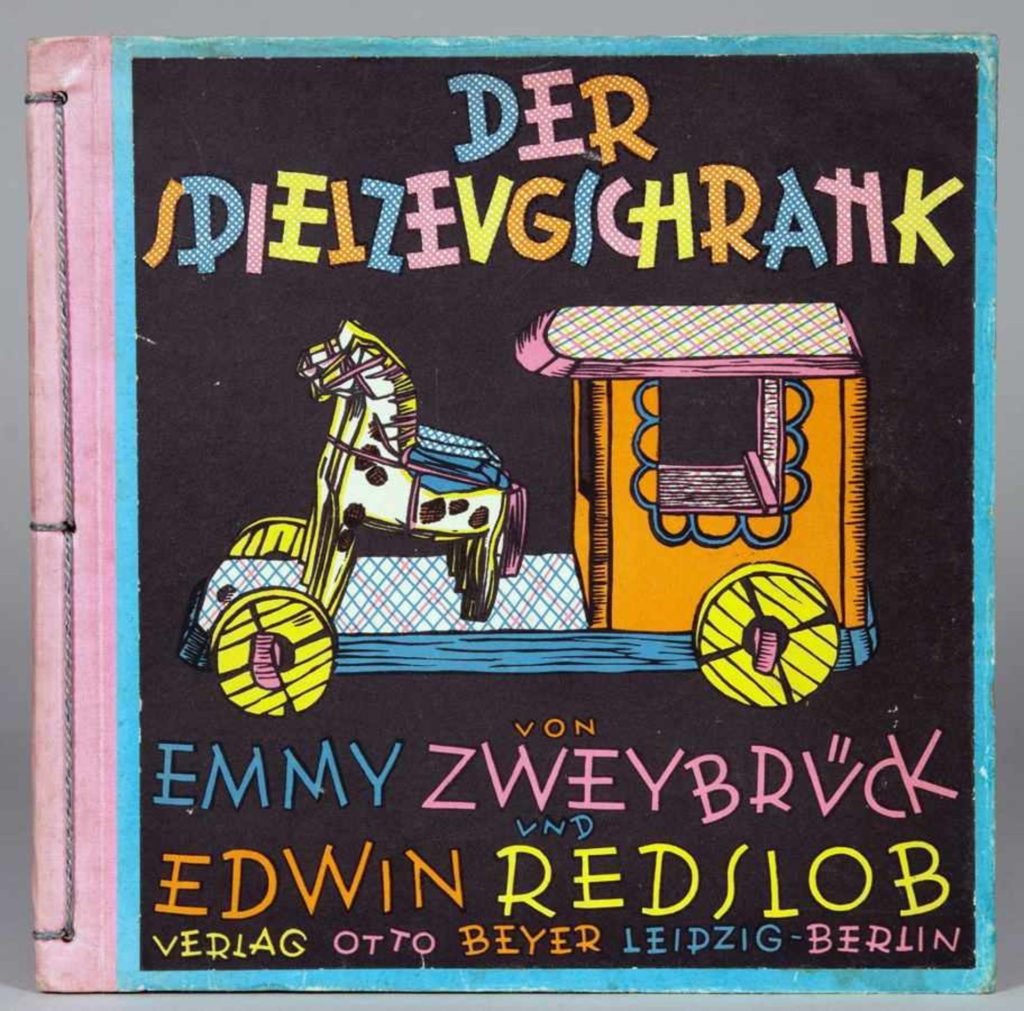

Like many of the other artists profiled here, children’s book illustration represented a particular area of specialty for Austrian-American emigres like Zweybrück, often proving an important source of income in exile. Perhaps the highpoint of her work in children’s book illustration, however, ensued before her emigration in her 1934 picture book Der Spielzeugschrank (The Toy Cupboard, Fig 4), a collaboration with the German art historian and critic Edwin Redslob speaking to the artist’s lifelong fascination with folk art toys. Much like the cover image, which featured a simply-constructed horse and carriage toy, the book paired innovative verse with color woodblock prints (another area of specialization for female art students in Secessionist Vienna) executed in an electric palette of yellows, pinks and blues.

Despite her American renown in her own lifetime, the reputation of Zweybrück has languished in comparison to that of Cizek. Perhaps it is because it is difficult to historicize the legacy of an artist whose legacy remains intangible, through her work as a teacher of children and amateurs. Perhaps it is because her legacy remains bound up in gendered hierarchies of media, material and technique that still guide conventional art historical narratives. Indeed, for ‘serious’ art historians, it is perhaps still uncomfortable to fathom that children’s books like The Toy Cupboard could be the nexus of avant-garde developments. In our talks, podcasts and blog posts, Creativity from Vienna to the World hopes to contribute to rethinking these hierarchies and valorizing the transmission of historically feminine artistic practices, media and modes of information between Central Europe and the United States.

[1] Cizek, Curriculum Vitae, Cizek Nachlass Archivbox 6.3.1, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, 16.

[2] Cizek, Curriculum Vitae, Cizek Nachlass Archivbox 6.3.1, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, 3.

[3] Cizek, Curriculum Vitae, Cizek Nachlass Archivbox 6.3.1, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, 3.

[4] Georg von Terramare, Schule und Werkstätte Emmy Zweybrück Wien (Wien: ÖWB, 1918), 12.

[5] Emmy Zweybrück Hands at Work (Sandusky, Ohio: Prang/American Crayon Company, 1946), 43.

[6] Ibid.,4

[7] Zweybrück-Prochaska, The Stencil Book: The Modern Art Methods of Professor Emmy Zweybrück (New York: American Crayon Company, 1935), 3.

[8] Zweybrück, Hands at Work, 26.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Terramare. Schule 14